I remember some national magazine or other publishing a humorous “interview” with Yoda in the summer of 1980, when The Empire Strikes Back was new and so was Yoda. Yoda answered questions on the topics of the day in his cockeyed syntax. (I remember the piece closing with Yoda asking, “Any more questions, have you?” and the interviewer responding, “Yes: who shot J.R.?“) Among the subjects covered in the interview was Superman the Movie — specifically, its opening credits, in which spectacularly animated names whoosh though interstellar space. Yoda said something like, “Oh yes, flying letter storms. Get them all the time on Dagobah, we do.”

That the article should touch on the opening credits — the credits — of another, unrelated movie more than a year and a half old, at a time when Empire was eclipsing everything else in the pop culture landscape, should give you some idea of the impression that Superman‘s credits made. They nearly upstaged the entire movie that followed, and decades later it’s those credits, set to John Williams’ unabashedly rousing march, that hold up better than most of the rest of the film.

That was almost all I had on the subject of opening credits until I mentioned to my wife Andrea that I would be participating in this blog-a-thon. Andrea, who routinely professes ignorance of and disinterest in film lore, proceeded to rattle off a series of terrific suggestions that I am embarrassed not to have come up with myself. So herewith, a few words on a few more memorable opening credits.

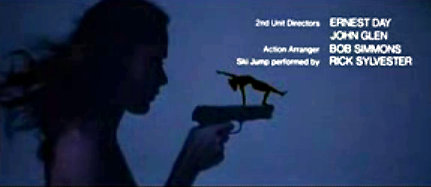

No discussion of memorable opening credits would be complete without mentioning the James Bond series. (Not that I’m aiming for anything like completeness.) The first film, Dr. No, doesn’t count, but it’s interesting in the way it doesn’t count: its credits are jazzy and abstract, which might have set the tone for the whole series if it had begun in the late 50’s rather than in the early 60’s. But Camelot and the Playboy era rode up alongside the James Bond series and the tone became somewhat different. The opening credits for the next film, From Russia With Love, created the template for the rest of the films: an imperfectly seen, mostly unclad beauty writhing athletically on screen. Later films, most of them with their title sequences designed by Maurice Binder (who had done the first two too) had variations on this theme: female silhouettes dancing and multiplying across the screen. When handguns appeared, the formula was complete. The pinnacle must have been The Spy Who Loved Me: Roger Moore and some nude women in silhouette, performing gymnastics on the silhouettes of handguns.

Maurice Binder is long gone, alas, but the latest Bond credits, for Casino Royale, are superb: paying homage to the old formula while modernizing with some (non-obnoxious) computer graphics and a considerably more serious tone emphasizing the consequences of violence (as silhouettes battling Bond disintegrate into heart, diamond, spade, and club symbols) rather than the glamour of girls and guns.

The Pink Panther (1963) had an opening credits sequence so memorable it spawned its own cartoon series — even though the film itself was a live-action farce about a diamond heist, not about an animated, rose-hued feline.

The Pink Panther (1963) had an opening credits sequence so memorable it spawned its own cartoon series — even though the film itself was a live-action farce about a diamond heist, not about an animated, rose-hued feline.

Robert Altman’s The Player opens with credits over a long, complex tracking shot — a single take several minutes long, shot with a single camera following several characters and actions in various locations around a complex set. During this sequence, one character mentions the brilliant tracking shot that opens Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil, making it a self-referential joke with plenty of inside-Hollywood references, which is exactly what the rest of the film delivers, too.

But no opening credits capture in microcosm both the psychology and the structure of the film to follow better than those in Memento. A Polaroid of a dead man fades to white. The movie is running in reverse and the Polaroid is un-developing. As the credits end, the blank film disappears into a camera, the flash bulb pops, a bullet flies back into a gun, and the dead man comes back to life.

The Polaroid has been taken as a memento of a violent deed committed by Leonard Shelby who, because of a head injury, lacks the ability to form new memories. Like the Polaroid-in-reverse, his experiences fade in just a few minutes. His life is defined by Polaroids like these, which he snaps and organizes to keep track of people, places, and events that he can’t remember on his own. The story is told in two tracks: one whose scenes are in black and white and appear in chronological order; and another, intercut with the first, whose scenes are in color and, like the fading Polaroid, appear in reverse.