Once, in a Warhol team brainstorming meeting, I had a pretty good idea.

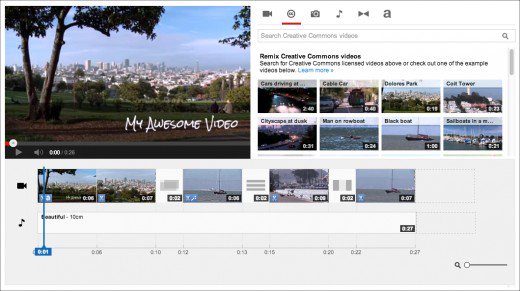

Warhol was the team responsible for the YouTube video editor, which was sometimes described as “iMovie in the cloud.” You could assemble new videos out of pieces of old ones, apply various special effects, add titles and transitions and so on, all in your web browser. It was pretty sweet.

There were some basic features we knew we needed to add to the editor. “Undo,” for example. Fast “scrubbing” through clips, and easy clip splitting and merging. Audio “ducking” and “pre-lap” and “post-lap.”

But in this meeting we were brainstorming ideas that could distinguish us from tools like iMovie, rather than merely achieve parity with them. What’s something that a YouTube-based video editor could do better than others?

To me the answer was clear: it could use YouTube’s unfathomably vast collection of videos as a stock-footage library, allowing users to create mashups from among billions of source clips.

There was one problem: nearly all those billions of videos had been uploaded under the terms of the standard YouTube license, which prohibited third parties from using videos in novel ways (ways that the original uploader might not approve of, after all). True, there was an option to upload your video under a Creative Commons license that did allow reuse by others. In fact I had personally worked on adding that option. But that option was not well-known, and hadn’t existed for long, and it required uploaders proactively to choose it, so only a tiny fraction of the videos on YouTube were licensed that way. The overwhelming majority were legally unavailable to would-be masher-uppers.

My idea for fixing this was called “reactive licensing.” You could create a video in the editor using whatever clips you wanted, pulled from all over YouTube no matter how they were licensed, but you couldn’t publish your video until getting approval from the clips’ owners. You’d click a “request approval” button and we’d send a message asking those owners to review your video project. They could respond with “Approve,” “Reject,” “Ignore,” “Block,” etc. If you got all the needed approvals, your edited video would become publicly playable.

Reactive Licensing generated some excitement. Here was something that YouTube, and only YouTube, was perfectly suited for. I whipped together a working prototype and we were just about to staff the project when the Legal department quashed it. Turns out a prospective use of someone’s video in a mashup—even one visible to no one but the creator and the owner—still violates the terms of service.1

Some time much later, Legal pushed through a change to the standard YouTube license (for unrelated reasons), and now Reactive Licensing became feasible! A couple of us on the Warhol team got excited again, and I started gearing up a development effort. But things had changed since I’d first conceived of Reactive Licensing. For one thing, both management chains—engineering and product—had been entirely replaced, from my boss all the way up to and including the CEO of Google. There were a couple of departmental reorgs thrown in to boot. For another, Google had become fixated on mobile computing, determined not to miss the boat on that trend as it felt it had with social networking. Everything that wasn’t a mobile app or couldn’t be turned into one became a red-headed stepchild, and the video editor was fatally desktop-bound. Finally, the creator and chief evangelist of the Warhol project had left to go work at Facebook. With his leadership, YouTube had harbored an institutional belief in the importance of balancing video-watching features with features for video creators and curators. Now, despite my efforts to keep it alive, that belief seemed to have departed along with him and the other managers who had supported it. The priorities that came down to the Warhol team now amounted to building toy apps that barely qualified as video-creation tools, such as the Vine workalike, or the thing for adding fun “stickers” to a video. (“Wow!”)

By that point my days at YouTube were numbered. This stuff simply wasn’t interesting—not to me, nor (I was sure) to our users. There were many interesting things we could have been doing, and that we knew our users wanted, but my strenuous efforts to make any of those happen were all denied.

My days at YouTube had seemed numbered once before, years earlier, after a frankly undistinguished tenure on two other teams that held little interest for me.

Back in those days, it was Google’s policy not to hire engineers for any specific role, but to hire “generalists” whom they felt could learn whatever they needed to know for wherever Google most needed them. I knew this when they hired me, but I still expected they’d put me on their new Android team (because I’d just finished 5+ years at Andy Rubin’s previous smartphone startup, Danger) or on their Gmail team (because I’d spent most of the preceding two decades as an e-mail technologist). I was surprised and a little disappointed when they put me at YouTube instead. I had no particular interest in or knowledge of streaming video. But more than that: YouTube was and is designed to keep you in a passive, semi-addicted state of couch potatohood, for which I was philosophically misaligned. I wanted to produce tools people could use. I wanted to empower the little guy and disintermediate the gatekeepers. Working on e-mail all those years, I’d been able to tell myself I was improving the world by making it easier for people to communicate with each other. Helping YouTube reach a milestone like a billion hours of watched video per day failed to move me.

On the other hand, Google was the Cadillac of software engineering jobs, and in those days it was still doing pretty well at living up to its “don’t be evil” motto. That, and the proximity of the YouTube office—half an hour closer to home than the main Google campus—was enough to energize me for a while… but only for a while.

If I hadn’t learned of the Warhol project, or if I’d been unable to transfer onto that team, my time at Google would have been over after two mostly forgettable years instead of seven mostly exciting ones. I hadn’t dreamed it was possible to build a working video editor in a web browser, but once I knew it was, I was hooked on the idea of delivering an ever more powerful creative tool to aspiring moviemakers who lacked the fancy computers and software they would otherwise need. To me it was the early days of desktop publishing all over again, but for video. Here at last was a niche at YouTube that wasn’t about driving increased “watch time.” It was about nurturing artistic expression.

We had big plans. We had working prototypes of a variety of special effects. We would build “wizards” that could make suggestions about shot sequences and pacing. We would give guidance on composition and color. We would commission educational materials from professional filmmakers. It would be “film school in a box.”

But even at its height, the Warhol project never quite got the resources or the marketing it needed, and certainly not enough executive leadership. Only seldom did we get to add one of the essential missing features we needed (like “undo”), to say nothing of the ones on our blue-sky wishlist. The rest of the time we were diverted onto other corporate priorities, such as specialized video-editing support for the short-lived Life In a Day tie-in, or addressing some complex copyright issue, or fixing bugs and performance problems.

Still, the YouTube video editor was well-loved and well-used by a small, dedicated group of users in the know. I myself relied on it while my kids were growing up for sharing well-edited videos of them to the families back east. But given its declining importance to YouTube’s management, it was just a matter of time before they killed it, like so many other beloved but neglected projects at Google. And now that inevitable day has come: the YouTube video editor will be discontinued on September 20th.

- For you copyright nerds: This was due to “synchronization rights,” an aspect of copyright that prohibited us from combining two videos in a way that could be construed as synchronizing one to the other. The design of the Warhol service was such that the edited video was created on our servers, and the result streamed to the user’s computer. If we could have arranged for the actual edits to happen on the user’s computer—ironically, the way iMovie works—we would have sidestepped the sync-rights issue. While not impossible, that would have been a cumbersome experience that defeated the purpose of a cloud-based video editor.

Sync rights doomed another feature I’d hoped to create: “serendipitous multicam.” I was at a school play at my kids’ elementary school when I realized that nearly all the parents were shooting the same video. Several of them would later upload their videos to YouTube. If it weren’t for sync rights, YouTube could identify clusters of videos all recording the same event (using Content ID, the same audiovisual matching system used for detecting illicit uploads of copyrighted material), arrange them on a common timeline, and present them as different “camera angles” in a video-editing project, allowing everyone to stitch together their own best-possible movie from them. [↩]