One day in the summer of 1979, when I was not quite 13 years old, I opened a newspaper and learned not only that Star Wars was being re-released to theaters (ending a long drought — in those days there was no other way to see it), but that it would be preceded by a trailer for next year’s sequel, The Empire Strikes Back.

I fairly rocketed out of the bungalow, whooping and hollering, to spread the news. It was the first I’d heard that a sequel was in the works, and that the Star Wars oeuvre, which — can you imagine? — was all of two hours long,1 was about to be doubled.

The nine months between that August and the following May were the longest of my life. Beginning in February or so, desperate for crumbs — there was no TMZ or EW to keep me abreast of production news — I began cutting short my subway ride home from school each day, exiting at Woodhaven Boulevard to enter the Sam Goody music store that was there then, to see if they had the soundtrack album in stock yet. Invariably they didn’t and I’d walk the remaining mile and a half home.

…Until the day, a couple of dozen tries later, that they did have it in stock! I almost couldn’t believe it. I bought it and ran it home to play it. There, just as I expected, was the opening trumpet blast and fanfare, just as in the first movie (but was that a slight difference in instrumentation I heard? and oh! surprise! the fanfare now ends on a higher note than before). As I listened to the new but occasionally familiar music I scoured the liner notes for what information I could about the movie, which was still interminable weeks away. An asteroid field scene — cool! Jedi training! A city in the clouds! Hmm, “the effigy of Han Solo” — I didn’t like the sound of that (after I looked up the meaning of “effigy”).

The new Imperial March was impressive, of course. Princess Leia’s new theme was pretty, but it left me without the profound sense of yearning that the concert version of her original theme gave me three years earlier. Unable to visualize the on-screen action yet, I found much of the album a lot less listenable than my trusty old Star Wars LP’s, but I did play the more thrilling pieces to death — “The Asteroid Field” and “Hyperspace.”

Honestly, I don’t know if I would have made it those last few weeks before the movie’s premiere if it hadn’t been for John Williams’ music to tide me over. Now, oddly, decades later, my boys walk around the house humming the same John Williams tunes that I once did — with a few notable additions, such as his “Duel of the Fates,” a composition whose musical qualities are conspicuously out of proportion to the caliber of the movie it appears in.

But that’s always been true. The presence of a John Williams score in a bad movie can elevate it to watchability, even respectability. In a decent movie, his music is still usually the best thing about it. (I’m looking at you, Superman. And where would Close Encounters have been without him?) And even when a great movie has a John Williams score, long after one’s appetite for watching the movie has flagged, it’s the music that it’s possible to enjoy over and over without limit.

- Er, not including a certain very forgettable TV special. [↩]

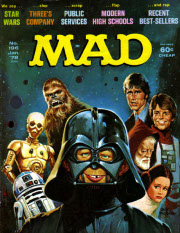

Maybe it’s Mad magazine’s fault for calling her Princess Laidup in their parody. Maybe the fact that

Maybe it’s Mad magazine’s fault for calling her Princess Laidup in their parody. Maybe the fact that