If I’d had any idea how 2016 was going to go when it began I never would have greeted it so cordially.

-

Welcome, 2016! I am excited to discover what awesomeness you have in store for us all.

-

It's been a couple of years and I should be over this but I'm not: it has bothered me all along that the anachronistic word “fractal” is in the lyrics of the most popular song from Frozen.

I just can't Let It Go.

-

In the JJ Abrams universe, you need only look up into the sky of one planet in order to witness the cataclysmic events taking place on another light-years away, even in broad daylight.

-

[The 50th anniversary of the premiere of the 1960's Batman.]

Pow! Bam! Sock! Oof!

12 January

-

We didn't win the $1.5 billion Powerball last week. But I can't bring myself to throw away the lottery ticket because, you know, clerical errors happen all the time.

-

Realization: Donald Trump is The Mule from Foundation and Empire, disrupting what should be the normal flow of history via strange powers of mental subversion.

-

Astonishing, depressing, and completely fascinating: the detailed story of the original negative of Star Wars and how it degraded to total crap.

Saving Star Wars: The Special Edition Restoration Process and its Changing Physicality

-

Take a Dixon-Ticonderoga pencil and some white-out. White out parts of the name Ticonderoga, leaving the word “cider.” Phonetically, it now says “Dick's inside 'er.”

Archer shared this trick with me recently. He learned it from his peers. I think he was testing to see whether he'd get in trouble for knowing this.

For my part, I was impressed. You have to white out just part of the N in Ticonderoga to turn it into an I! Whoever came up with that showed real dedication to the pursuit of a microscopic naughty thrill. That is just so middle-school.

-

The best thing I've read explaining Trump's popularity. Read it. Read it.

Trump Supporters Aren't Stupid

-

Just woke up from a racial-harmony dream. It was beautiful, man.

-

How I know that either time travel is impossible or Trump won't win the presidency: no time travelers from the future are appearing to stop him.

-

High on the list of things you never want to read on nextdoor.com is that a scorpion once was seen in the backyard of the house next to yours.

-

Of all the people not to invite to a party, the Goddess of Discord? Whose bright idea was that? That was never going to end well.

-

Among my news headlines this morning, both Donald Trump's week and Gmail's April Fools gag were described as “terrible, horrible, no good, very bad.”

-

“Smith & Noble”?

How do Barnes and Wesson feel about this?

-

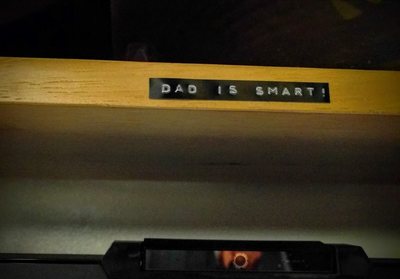

Feeling appreciated.

-

Archer asked me the other day, “Would you rather have time and no freedom, or freedom but no time?”

While I was trying to figure out how to respond, he added this clarification: “So, kid or adult?”

I was speechless.

-

By a statistical fluke, I was considerably taller than all the other commuters around me on a crowded Muni train this morning. It was glorious.

-

[On the death of Prince.]

Thinking about the night in 1984 when Steven Stern and I wanted to enter the West 4th Street subway station but were prevented by a scary dude who ranted at us for a while about Purple Rain, which was then brand-new. After importuning us for a couple of minutes, he asked, “What's the best color?” Luckily, Steve had the presence of mind that I didn't, and he gamely answered, “Purple!” The dude said, “What's the best movie?” Steve said, “Purple Rain!” And the dude let us pass.

-

What I learned from rewatching Purple Rain last night:

-

It's OK to be a jerk if you're very talented and very sexy

-

If you're very talented and also funny, but not quite as sexy, you deserve to be pushed into a pile of garbage

-

Women are for sex

-

If you treat a woman as an equal partner you will fail to earn her loyalty

-

If you alternately slap her around and cuddle with her, she'll be yours forever

-

Fellow getting-old people: where is it possible to smell mimeograph fumes today, so younger generations can know what they're missing?

-

Ordered an egg cream at the Cowgirl Creamery milk bar in the Ferry Building. Got a cup of watery Ovaltine.

-

That gratifying feeling when you've been vaguely sick for a day or two and the thermometer finally validates all your complaining.

-

I don't watch Game of Thrones. But in my dream last night, I complimented Peter Dinklage on the fine job he's been doing on that show.

-

[On the plea for clemency by Brock Turner's father, based on the fact that Brock raped his victim for only twenty minutes.]

Dear Mr. Turner,

How many more minutes of rape would be needed, do you think, before your son would deserve a harsher penalty?

Just curious,

– Bob

-

[On the popularity of the Fall Out Boy song “Uma Thurman.”]

I hummed the theme from The Munsters before it was cool.

-

Attention young people: That scene in Jaws where Quint crushes a beer can in his hand, and Hooper lamely tries to match him by crushing his coffee cup? In 1975, crushing a beer can in one hand was in fact a manly display of strength, as cans were made of heavy steel, not flimsy aluminum.

-

To those Brexit voters now feeling remorse, and to everyone else watching who longs for a return to some version or other of the Good Old Days, please learn this lesson: there is no going back, there is only going forward. Even if it were possible to go back, and even if the Old Days were as Good as you think they were, the same forces that brought you to the hated present would still exist. Better to “launch and iterate” as we say in software engineering; “rollbacks” are always more costly than you expect.

-

This painted-on path-use indicator is surprisingly bumpy to roll over on a road bike. But, fun game: no bumps if you can roll through the stencil gaps in the wheels, plus you improve your cycling precision.

-

[On July 4th.]

240 years of the Declaration of Independence! 50 years of the Freedom of Information Act!

-

RIP Sydney Schanberg and Michael Herr, two extraordinary journalists who opened my young and naive eyes to some of the world's severest unpleasantness.

-

Remarkable long read convincingly explaining our worsening political dysfunction. Tl;dr – the system of party functionaries, horse trading, and smoke-filled rooms that we've spent a generation dismantling as undemocratic actually performed an essential role in moderating our politics.

How American Politics Went Insane

-

I've been immersing myself in the headlines of 1966 all year, while maintaining its1966.tumblr.com. Though it may be cold comfort, know that as bad as things seem in the world right now, they're much better than they were then.

-

“Jeb Bush and Mitt Romney would be spinning in their graves, if they were dead, and right now they wish they were.”

“Trump is dangerous precisely because he does not seem like a real person, and the people voting for him do not think they’re voting in a real election with real consequences.”

Can't wake up from this nightmare.

His dark materials: After that diabolical, masterful performance, Donald Trump could easily end up president

-

“All republics are fragile; the [Weimar Republic], like the Third French Republic it paralleled, did not commit suicide—it was killed, by many murderers, not least by those who thought they could contain an authoritarian thirsting for power.”

“No reasonable person, no matter how opposed to her politics, can believe for a second that Clinton’s accession to power would be a threat to the Constitution or the continuation of American democracy. No reasonable person can believe that Trump’s accession to power would not be.”

Being Honest About Trump

-

“Damn all the people who will vote for him, and damn any progressives who sit this one out because Hillary Rodham Clinton is wrong on this issue or that one. Damn all the people who are suggesting they do that.”

This Isn’t Funny Anymore. American Democracy Is at Stake.

-

Are you one of those who hears comparisons of Trump to Hitler and secretly thinks, “Maybe that's just what this country needs right now”?

If so, may I suggest you take another look at how that turned out for Germany?

-

I love that “old Bob” (as opposed to “new Bob”) is the same as “young Bob” (as opposed to “old Bob”).

-

This is excellent, even if you're not interested in learning web design.

Web Design in 4 minutes

-

50 years ago tomorrow, a price increase of one cent per quart of milk was front-page news in the New York Times.

-

It's cool how the Overton Window is moving to drain the phrases “his husband” and “her wife” of their strangeness.

-

The original is in my pantheon of perfect films. It cannot be improved upon.

Rocketeer reboot in development at Disney

-

Some guys, when not wearing their sunglasses, perch them on the back of their heads, facing backwards. That seems like it should be insufferably dopey, but for some reason I can't figure out, it's just not.

-

Trump's eagerness to use nuclear weapons reminded me of something.

Forget about the badge! When do we get the freakin guns!

-

The moment we've all been waiting for: when Donald Trump's strength and momentum are finally revealed to be merely bluster and frenzy.

-

It's not really the future yet if I still have to fill out two of these by hand every year.

-

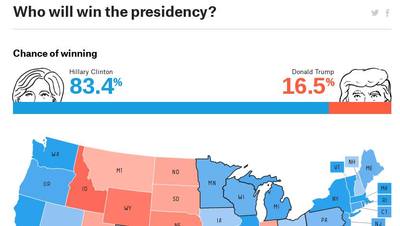

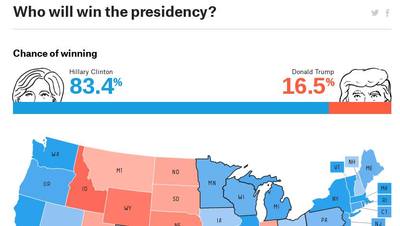

Don't want to check fivethirtyeight.com too often. Afraid I'll jinx it.

-

Embarking on a five hour listen. Only Dan Carlin could make that a pleasant prospect.

King of Kings III

-

My long search is over! Pizza in San Francisco that actually is “NY style” instead of being falsely advertised as “NY style.”

Pizzeria Avellino

-

<3

-

Lenny Bruce died fifty years ago this month. Writing challenge: Imagine he'd lived and been given his own sitcom, like Seinfeld and others he paved the way for. What would an episode of that have been like? Go.

-

A banner day for Chain.com!

-

#TIL about UEFI locking. Evil – worse by far than browser exclusion, which resulted in an anti-trust judgment against Microsoft in the 90's. It's preventing me from installing Linux on my new Dell box, and I anticipate a rough time getting satisfaction from Dell customer support.

-

Finn the human!

-

GASP! “The first ever roguelike celebration”!!

There's virtually no chance I'll be able to go on such short notice, but if you can make it, please report back.

Roguelike Celebration

-

Please let this be peak Trump.

-

[The home stretch of the presidential campaign.]

Go team Age of Enlightenment!

-

So you're a Trump voter – or at least, you were. Now you're starting to have your doubts. But everyone in the lamestream media is insisting that you MUST NOT vote for him, and you'll be damned if you'll ever take THEIR advice – or look like you're taking it.

You need a way to reach a no-vote decision that preserves your independence, that has nothing to do with all the criticisms of how Trump throws his weight around, which is secretly why you like him.

Try this: if he's elected President, the revelations so far about his likely lawbreaking (violating the Cuba embargo, flouting charitable foundation rules) will be just the beginning. He'll be more beset by investigations and allegations than Bill Clinton was, or even Nixon. Even if you think he'd do a good job, he WON'T GET THE CHANCE.

-

Apparently I work just down the street from the Mertin Flemmer Building.

-

There are plenty of weird Tumblrs out there. This is one of them.

redandjonny

-

When we visited Thailand several years ago, our taxi driver told us in his broken English about why their king was so beloved: “No drink, no smoke, one wife, no girlfriend.” RIP King Bhumibol.

-

This is how we defeat Trump.

-

Short but damn good writing.

The Agonizing Essence of Donald Trump, in One GIF

-

-

After decades of working almost exclusively on closed-source projects whose potential for actually improving the world was limited at best (never mind what the marketers always said), it gives me tremendous pleasure to be able to present the open-source and actually transformative fruits of my past year's labor, and that of what must surely be among the best small software teams ever assembled.

Our site: https://chain.com/

Our short explanatory video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bK6wHW1K9jM

Our whitepaper: https://chain.com/docs/protocol/papers/whitepaper

Our CODE!!! https://github.com/chain/chain

Our press: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-10-24/blockchain-hype-takes-hit-as-chain-releases-code-for-all-to-use http://fortune.com/2016/10/24/visas-blockchain-chain-open-source/

-

Funny birthday cards from my kids.

-

Happy fourth birthday, Pepper!

-

President Clinton's first official act when taking office in January: she should pardon Donald Trump like Ford did Nixon. Not even kidding.

-

I doubt anyone would like to see Trump have to answer for his lifetime of bullying behavior (in its many forms) more than I would. But if we pursue that beyond a Clinton victory we'll be no better than the Trump voters calling for Clinton blood.

Here's what pardoning Trump would (hopefully) achieve:

-

Disarm the Trump true believers who are bracing to defend their hero against Crooked Hillary;

-

Demonstrate, in clear contrast to what Trump has promised, that in America politicians do not use the machinery of government to persecute their opponents;

-

Begin to mend our political rift;

-

Ensure that the national conversation moves beyond Trump as quickly as possible;

-

Consign Trump to national irrelevance, which is as good as jail for him.

Trump loves nothing more than a fight. Let's take that away from him.

-

[Just before Election Day.]

These last few days are increasingly hard to take. I think I need to start drinking and not stop until Wednesday morning.

-

One is a boor and the other's a bore

Neither one's rhetoric soars

Can't help but cringe at the lunatic fringe

Or the one I've no eagerness for

One is too bold and the other's too cold

Also they're both pretty old

After eight years of class how'd we get to this pass?

The current guy: he broke the mold

-

Good morning, America! I'm gonna vote SO HARD today.

-

Earlier generations of Americans have had their worthy challenges: throw off monarchy, end slavery, defeat the Axis, etc. We are the coddled and too-comfortable product of their efforts and, in historical terms, haven't done a single thing to earn our privilege. Trump is both the perfect symbol of that and, at last, our worthy challenge.

-

To the extent that Trump voters have been feeling fear and disenfranchisement and needed to spread those feelings around: fair, and mission accomplished.

-

A few hopeful thoughts from the group commiseration that took place at work today:

First, Hillary eked out a popular vote victory despite being, let's face it, a not very inspiring candidate. With someone who's energizing and totes less baggage, the sky's the limit.

Second, we sent a Latina, a Thai woman, and a female amputee to the Senate. That's not nothing.

Third, crisitunity: clearly the Democratic party needed to be destroyed to be saved insofar as it wasn't working for very large numbers of Americans whose votes it took for granted. Under a President Clinton that would not have happened (and the underlying problems might have gotten even worse); now it can.

-

Worth hearing: yesterday's Fresh Air interview with journalist James Fallows, who's been criss-crossing America visiting small usually overlooked towns to understand their politics, discovering that in most places, the people there believe they're doing well, and even have progressive values, but also believe, thanks to the constant-crisis media, that the rest of the country is going to hell.

How Trump Broke Campaign Norms But Still Won The Election

-

Ugh, just got an image in my head of what Donald and Melania will get up to on the first night in the Oval Office.

-

Cheer up! The country is not dominated by swarms of hateful bigots you've been underestimating.

https://twitter.com/tegmark/status/796387518803546112/photo/1

-

Deplorable.

Women, minorities, immigrants, genderqueers: I am a white man on your side.

Day 1 In Trump's America

-

Keep voting.

The Official #GrabYourWallet Boycott List of Companies that Do Business with and/or Back the Trump Family

-

Everyone's wondering what Trump will and won't actually do as President. To me it seems clear: he couldn't care less about any particular policies except insofar as they allow him to humiliate powerful people. Whatever results in more abasement before him, that's what Trump will choose.

-

I signed, and donated.

Tell Donald Trump to Reject Hate and Bigotry

-

Dear Donald Trump,

I get it, you had to prove you could be elected President. You have to be the biggest and the best, and as long as other people could win the Presidency, there's always been someone bigger and better than you.

But you're still not there yet. You won the election but now you must be judged alongside dignified, thoughtful, compassionate men like Washington, Lincoln, Roosevelt (either one, pick your favorite), Eisenhower, and Kennedy. You won't be the biggest or the best unless you can stop doing what's right for Donald Trump and start doing what's right for your fellow Americans. If you can, I think you'll find that that is what's right for Donald Trump.

-

I listen to podcasts on my commute, and I'm pretty backlogged. I'm hearing shows that were recorded in October. Mostly they don't deal with politics, but of course the subject of the election still comes up from time to time. All those poor naive people of a few weeks ago who have no idea how things are about to turn out…

-

Gazing out the window of the ferry at the whitecaps and the swells sliding by. Glanced at the laptop screen of a fellow commuter and it appeared to move and flow like whitecaps and swells. Cool.

-

Presenting my Sunday project: Trumpit, a Chrome extension that rewrites occurrences of Donald Trump's name in web pages. From the README:

Do not allow the press to normalize the things that Trump has said, done, and failed to do on the way to the White House.

Every mention of his name should be a stark reminder of who and what he is.

This extension makes that literally true.

Trumpit

-

An updated version of my Chrome extension is available that adds tooltips: hover your mouse over e.g. “Donald J. Tax Evader” to get a randomized, detailed reminder of some outrage such as:

Donald Trump said “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn't lose voters.”

Trumpit

-

Happy birthday mom. If you were still around, I know you'd be over the moon about your wonderful grandsons, in love with Chris Pratt, sick with outrage about Trump, and stubbornly refusing to understand my explanations about the blockchain. And we would constantly be talking about all those things.

-

Holiday movie report:

Doctor Strange: even this straight guy is in love with Benedict Cumberbatch. Never mind how they executed those special effects, how did they even conceive them?? Also, perfect “solution” to the movie's main plot and character dilemmas.

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: lots of inventive depiction of magic, but no character arcs or mystery, yawn.

Moana: tears-streaming-down-face perfection.

-

Moderate Republican senators surely feel like the party has left them behind. If I were a multimillionaire, I would be meeting with them right now saying, “I have $20 million in cash for the first of you to switch to the Democratic party, $5 million for the second, and $1 million for the third.”

-

20 lessons from the 20th Century. Wise (and practical) words against authoritarianism by Yale historian, Holocaust expert, and Member of the Council on Foreign Relations Timothy Snyder:

“1. DO NOT OBEY IN ADVANCE. Much of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then start to do it without being asked. You've already done this, haven't you? Stop. Anticipatory obedience teaches authorities what is possible and accelerates unfreedom.

2. DEFEND AN INSTITUTION. Follow the courts or the media, or a court or a newspaper. Do not speak of “our institutions” unless you are making them yours by acting on their behalf. Institutions don't protect themselves. They go down like dominoes unless each is defended from the beginning.

3. RECALL PROFESSIONAL ETHICS. When the leaders of state set a negative example, professional commitments to just practice become much more important. It is hard to break a rule-of-law state without lawyers, and it is hard to have show trials without judges.

4. WHEN LISTENING TO POLITICIANS, DISTINGUISH CERTAIN WORDS. Look out for the expansive use of “terrorism” and “extremism.” Be alive to the fatal notions of “exception” and “emergency.” Be angry about the treacherous use of patriotic vocabulary.

5. BE CALM WHEN THE UNTHINKABLE ARRIVES. When the terrorist attack comes, remember that all authoritarians at all times either await or plan such events in order to consolidate power. Think of the Reichstag fire. The sudden disaster that requires the end of the balance of power, the end of opposition parties, and so on, is the oldest trick in the Hitlerian book. Don't fall for it.

6. BE KIND TO OUR LANGUAGE. Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking, even if only to convey that thing you think everyone is saying. (Don't use the internet before bed. Charge your gadgets away from your bedroom, and read.) What to read? Perhaps “The Power of the Powerless” by Václav Havel, 1984 by George Orwell, The Captive Mind by Czesław Milosz, The Rebel by Albert Camus, The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt, or Nothing is True and Everything is Possible by Peter Pomerantsev.

7. STAND OUT. Someone has to. It is easy, in words and deeds, to follow along. It can feel strange to do or say something different. But without that unease, there is no freedom. And the moment you set an example, the spell of the status quo is broken, and others will follow.

8. BELIEVE IN TRUTH. To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights.

9. INVESTIGATE. Figure things out for yourself. Spend more time with long articles. Subsidize investigative journalism by subscribing to print media. Realize that some of what is on your screen is there to harm you. Bookmark PropOrNot or other sites that investigate foreign propaganda pushes.

10. PRACTICE CORPOREAL POLITICS. Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.

11. MAKE EYE CONTACT AND SMALL TALK. This is not just polite. It is a way to stay in touch with your surroundings, break down unnecessary social barriers, and come to understand whom you should and should not trust. If we enter a culture of denunciation, you will want to know the psychological landscape of your daily life.

12. TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE FACE OF THE WORLD. Notice the swastikas and the other signs of hate. Do not look away and do not get used to them. Remove them yourself and set an example for others to do so.

13. HINDER THE ONE-PARTY STATE. The parties that took over states were once something else. They exploited a historical moment to make political life impossible for their rivals. Vote in local and state elections while you can.

14. GIVE REGULARLY TO GOOD CAUSES, IF YOU CAN. Pick a charity and set up autopay. Then you will know that you have made a free choice that is supporting civil society helping others doing something good.

15. ESTABLISH A PRIVATE LIFE. Nastier rulers will use what they know about you to push you around. Scrub your computer of malware. Remember that email is skywriting. Consider using alternative forms of the internet, or simply using it less. Have personal exchanges in person. For the same reason, resolve any legal trouble. Authoritarianism works as a blackmail state, looking for the hook on which to hang you. Try not to have too many hooks.

16. LEARN FROM OTHERS IN OTHER COUNTRIES. Keep up your friendships abroad, or make new friends abroad. The present difficulties here are an element of a general trend. And no country is going to find a solution by itself. Make sure you and your family have passports.

17. WATCH OUT FOR THE PARAMILITARIES. When the men with guns who have always claimed to be against the system start wearing uniforms and marching around with torches and pictures of a Leader, the end is nigh. When the pro-Leader paramilitary and the official police and military intermingle, the game is over.

18. BE REFLECTIVE IF YOU MUST BE ARMED. If you carry a weapon in public service, God bless you and keep you. But know that evils of the past involved policemen and soldiers finding themselves, one day, doing irregular things. Be ready to say no. (If you do not know what this means, contact the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and ask about training in professional ethics.)

19. BE AS COURAGEOUS AS YOU CAN. If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die in unfreedom.

20. BE A PATRIOT. The incoming president is not. Set a good example of what America means for the generations to come. They will need it.

ETA: Feel free to share, but please copy + paste into your own status or else it will not be viewable to all of your friends.”

-

When I shared this link earlier this year, I wrote:

“Remarkable long read convincingly explaining our worsening political dysfunction. Tl;dr – the system of party functionaries, horse trading, and smoke-filled rooms that we've spent a generation dismantling as undemocratic actually performed an essential role in moderating our politics.”

Reposting now with the observation that the Electoral College is one of our few remaining “smoke-filled rooms.”

How American Politics Went Insane

-

What are we talking about now? Whether flag burners can or should be punished.

Why are we talking about it? Was there some flag-burning emergency? No, we're talking about it because of a Trump tweet.

What are we talking about less as a result? Trump's baseless allegations of voter fraud and his outrageously corrupt cronyism.

Don't be fooled.

-

And now for something completely different: an old-timey tune that Google Play Music threw into my playlist this morning. Sound familiar?

Gracie Fields – Sing As We Go

-

Not mentioned in this article: the Big Mac was created to compete with an almost identical sandwich at a BOB's Big Boy restaurant in Pittsburgh; and it was named by an advertising secretary named GLICKSTEIN. For real!

Creator of McDonald’s Big Mac dies at 98

-

I keep hearing that demographics favor Democrats going forward, because young people overwhelmingly vote that way. But wasn't that also true in the 60's and 70's? Where are those young people now?

-

I wanted to know the meaning of some lyrics in a song from Moana. They're in some Pacific-islander language (Samoan, I think), so I went to Google Translate and selected “detect language.” It chose Japanese and gave me this translation:

Oh yeah

Muuuuuuuu

Do not worry about it

Oh yeah

Well, Fuh – Wah,

Naked rice cookies.

-

As a matter of Constitutional law, which is Obama's greater responsibility: to transfer power to Donald Trump on January 20th, or to refuse to?

Yes, he took an oath to preserve the Constitution, which mandates an orderly transfer of power; and we as a nation take rightful pride in our long history of peaceful changes of leadership.

But the President is also sworn to defend the Constitution – against, for example, those who with the help of adversarial foreign powers openly seek to undermine it. If such a figure manages to position himself, via deception and subversion of the democratic process, to receive that peaceful transfer of power, surely no reasonable interpretation of the Constitution requires that the country roll over and submit?

-

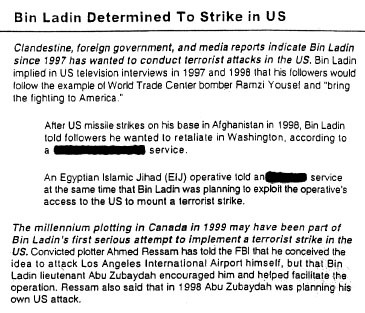

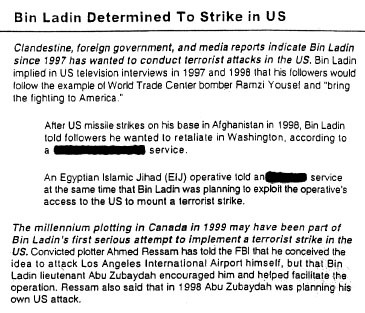

The president ignoring his presidential daily briefings… where have I heard that before?

-

Two questions for the Electors:

1. Which will you regret more in the future: blocking Trump, or not blocking him?

2. Which requires greater courage?

The answer to the second should inform your answer to the first.

-

“Republicans — led by a man who rage-tweets fake news in the middle of the night — are about to embark on a long voyage of turning every single thing they touch into garbage. There should be no Democratic fingerprints whatsoever on the coming catastrophe. Democrats must not give the imprimatur of legitimacy to the handsy Infowars acolyte who is about to take the oath of office. Not to get some highways built. Not to renegotiate NAFTA. Not to do anything.

At long last, Democrats must learn from their tormenters: Obstruct. Delay. Delegitimize. Harass. Destroy. Above all: Do. Not. Help. This. Man. Govern.”

It's time for Democrats to fight dirty

-

On the bright side, our collective odds of dying from cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and other infirmities of age have gone down! True, it's because our odds of dying from war, political violence, economic collapse, or diminished food/product/building safety standards have gone up, but always look for the silver lining, I say.

With electoral college vote, Trump's win is official

-

What positive, constructive things has the modern Republican party achieved at a national or state level?

This is a sincere request for information. It is not an invitation to heap scorn.

That said, it seems to me that the Republican party exists only to maintain its own power and help those who need help the least. It does this by systematically disenfranchising large numbers of voters, by persuading large numbers of other voters as to which of their fellow citizens they should mistrust and ridicule, and by (in the words of Thomas Jefferson) “refusing assent to laws the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”

There's also the wars and the economic mismanagement.

Those are all achievements, strictly speaking, but not positive, constructive ones. Can anyone credibly refute my view of the Republican party?

[No one meaningfully did.]

-

Close, Facebook, close. You're off by only 1,728 miles.

-

Santa came and ate half of a cookie we left out for him! The kids said, “Let's get a saliva sample from the cookie and DNA-test it to prove it's Dad!” While cleaning up after opening gifts, I ate the rest of the cookie, before they could collect the evidence. Oops. 😉

-

Rogue One is about stealing the Death Star plans. For months leading up to its release, Jonah and I have been saying “space heist!” to each other with mounting excitement. We got a gritty war thriller instead. It's good, but the world still needs its space heist movie.

-

In 1980, when we learned that The Empire Strikes Back was the fifth episode in a planned nine-movie series that wouldn't be complete until 2001, I worried that the cast might not survive long enough to tell the full story. (Mark Hamill had already almost checked out in his post-Star Wars car crash.) Then we learned that the only characters who would be in all nine films were the droids, and I relaxed a little. In 1983, Lucas said never mind, he was done making Star Wars movies, and though by then I cared less, I still breathed a sigh of relief. Then Disney bought Lucasfilm[*] and started a new series of sequels with the original cast, and my old worry returned. Today my decades-old fear came true.

RIP, Your Worshipfulness.

[*] – There may have been some other nominal Star Wars movies in the interim ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

-

I posted this earlier this year, and I’m sorry to say I no longer think this is true.

I’ve been immersing myself in the headlines of 1966 all year, while maintaining its1966.tumblr.com. Though it may be cold comfort, know that as bad as things seem in the world right now, they’re much better than they were then.

Then: Civilian casualties of U.S. military action widely protested (due in part to the draft)

Now: U.S. military action mostly out of sight, out of mind

Then: Widespread racial strife vigorously combated by federal government

Now: Racial strife tacitly encouraged by incoming government

Then: Congressional action on numerous matters of public import, including several unanimous votes on big bills

Now: Unyielding partisan obstruction on all matters of public import

Then: 10% of nation’s wealth concentrated among top 0.1%

Now: 25% of nation’s wealth concentrated among top 0.1%

Then: Batman didn’t casually kill bad guys by the dozen

-

Tl;dr – wide swaths of America now reflexively regard any story reported in e.g. the NY Times as false, no matter how well substantiated.

This weaponizes citizens against the country. More than Trump, more than Pence, more than Putin, more than anything, the right-wing propaganda apparatus is the enemy.

Fake News Is Not the Real Media Threat We’re Facing

-

I’m grateful to Wired for publishing

I’m grateful to Wired for publishing