It’s been over three months since way number eight, but there’s now a ninth way I’m like blogging-inspiration Ken Jennings: apparently I’m not the only one who has an odd compulsion to read car names backwards while I’m driving around town.

Atheism, the final frontier

The BBC has recognized outspoken atheist Richard Dawkins as their 2006 Person of the Year. That made me think of the original Star Trek.

When writing about the appeal of the original Star Trek it has become de rigeur to cite its optimistic vision for the future — in which war, racial strife, etc. have been overcome — especially since it appeared during the turbulence of the 1960’s. But I think the real answer is something deeper and more essential.

When writing about the appeal of the original Star Trek it has become de rigeur to cite its optimistic vision for the future — in which war, racial strife, etc. have been overcome — especially since it appeared during the turbulence of the 1960’s. But I think the real answer is something deeper and more essential.

First, a digression. In The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, the Baron, that lovable spinner of fantastical tall tales, is opposed by “The Right Ordinary Horatio Jackson,” a literal-minded and distinctly unlovable bureaucrat who prizes order and rationality over the creative chaos of the Baron’s world. The film depicts rationality robbing the world of adventure and romance.

First, a digression. In The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, the Baron, that lovable spinner of fantastical tall tales, is opposed by “The Right Ordinary Horatio Jackson,” a literal-minded and distinctly unlovable bureaucrat who prizes order and rationality over the creative chaos of the Baron’s world. The film depicts rationality robbing the world of adventure and romance.

American pop culture has always been hard on men of reason, who usually come off as amoral, insensitive, clumsy, narrow-minded, unpoetic, socially inept, or downright mad. Dreamers, lovers, men of action — they are the heroes, and anyone employing logic is a mere detractor if not an out-and-out villain.

In the popular imagination, the intellect is suspect. Thinkers in general, and scientists in particular, are a haughty elite, the priests and guardians of an occult sect with its own impenetrable apocrypha and incomprehensible dialects. They set themselves up as authorities on various subjects and make pronouncements based on arcane knowledge that are never to be trusted, because there’s always a contradictory pronouncement just around the corner.

But in reality, what can be more democratic than science? It’s the ultimate leveler; anyone can be an authority. Science isn’t a particular collection of knowledge or a particular place or particular people. Science is a method, famously encapsulated by Richard Feynman as: “1. Make a guess. 2. See if you’re wrong.” Anyone who thinks according to these rules, and follows fearlessly where the reasoning leads, is a scientist.

If democracy is the founding principle of America, science and rationality are its true religion. They are the bedrock on which its political and industrial institutions are built, even at times when science seems temporarily discredited by the prevailing political fashions of the day.

Yet, even as science is central to the American experience, it gets short shrift in popular culture. Often marginalized, occasionally trashed, seldom if ever was it celebrated properly — until Star Trek. The accomplishment of Star Trek, and the true source of its enduring appeal, was its portrayal of a future in which rationality does not kill adventure and romance but creates them, satisfying the unmet need of Americans to see their society validated — or, as one like-minded fan commented recently,

It isn’t Star Trek’s “optimism” that made it great. It’s the idea that in the future the Carl Sagans of the universe will be in charge and successfully run society on the principles of secular humanism and science while the George Bush and Dick Cheneys of the universe are Klingons. Star Trek is about the promise of a new Enlightenment […]

As a champion of romantic rationality and a lifelong Star Trek fan I am encouraged by the selection of Dawkins as BBC’s Person of the Year. Atheism has always been the belief-that-dares-not-speak-its-name. Even at the height of the Age of Reason, Thomas Jefferson, whom we might recognize as an atheist, called himself a Deist. But this news about Dawkins, and other harbingers (here, here, and here), suggest that atheism is coming out of the closet in a big way, which can only happen in an environment favorable to rationality. Can it be that the recent wave of anti-intellectualism in the Western world finally crested, crashed on the jagged rocks of the reality-based community, and is now receding?

That would be good news for the back-to-its-roots Star Trek movie now in development.

Numerology

A quick observation before heading to bed: this will be a good year because it ends in 007.

Proud papa alert

Jonah just read this book entirely on his own!

Update: The online version of this book doesn’t even contain all the pages of the printed version that Jonah read. Notably missing is the “Sam sat on Mat” part of the story.

Money-saving suggestion

Happy new year!

Undoubtedly one of the best times to be in the health-club business is shortly after the new year, when everyone makes a new year’s resolution to lose weight and get fit, then joins a gym in order to accomplish those goals. As health clubs know, the majority of those new memberships will be of people who don’t actually show up more than a few times to use the facilities — and the gym gets to keep their non-refundable membership fees running to the hundreds of dollars each. My guess is that the income from January alone probably keeps a health club going at least until swimsuit season starts looming near.

On the one hand, it’s hard to fault health clubs for this practice. If you decide to join a gym, pay your money, then don’t show up, whose fault is it, theirs? No. On the other hand, there’s a P.T. Barnum sucker-born-every-minute aspect to this practice that is vaguely distasteful to plain-dealing folks like myself, who insist on receiving money only for actual goods or services delivered. So here is a common-sense consumer-protection suggestion from me to you:

If your new-year’s resolution is to get fit and lose weight (which I encourage), don’t join a gym first. Do ten push-ups, ten squats, and ten leg-lifts every day for fourteen days. (My doctor once told me, when encouraging an exercise regime I was beginning: “Fourteen days makes a habit.”) At the end of that time, if you are still consistently doing your exercises and your enthusiasm hasn’t waned, then join a gym.

(Disclaimer: get a doctor’s advice [I’m not one], do proper warm-up stretches, etc.)

If you do resolve to get fit and lose weight in the new year, and you were inclined to join a gym but you took my suggestion and you ended up abandoning your fitness regime, I will gladly accept a donation of 10% of the health club membership fee that I saved you!

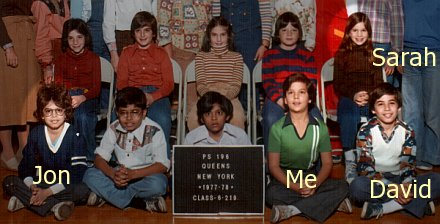

It was a wonderful life

Shortly after I wrote my eulogy for my childhood friend Jon, I sent a printed copy to his mother, who hadn’t heard from me, nor I her, since the 1970’s. After a few weeks she responded with a lengthy letter and a portfolio of Jon’s life: photos, writings, news clippings, accolades, stories about Jon, and finally many beautiful remembrances. I am happy to report that, short though Jon’s life was, it was rich and accomplished.

Jon was the editor-in-chief of his college humor newspaper. He earned a masters degree in sociology and a degree in law. As a legal intern he represented troubled youth in court, part of a child advocacy program. At the time of his death he was working to pass the bar exam, struggling with mounting medical problems arising from both his kidney disease and from a hepatitis infection he contracted from a transfusion years earlier. He was the first recipient, posthumously, of an award created in his honor, the Jonathan Roppolo Student Achievement Award of the Suffolk County Bar Pro Bono Foundation.

The other eulogies that Jon’s mom forwarded to me from friends and family were unanimous on many points: that Jon had exceptional intelligence, integrity, humor, and compassion; that he endured his disease and the tedious routines that went along with it entirely without complaint; that he had uncommon passion and drive; and that Jon made indelible changes for the better in those who knew him, as he did me.

All of which makes him out to be rather a saint, which may indeed be appropriate but is also rather depersonalizing. When I knew him he was just an uncommonly fun friend, part of my inner circle. We hung out, played games, hatched schemes, acted silly.

All of which makes him out to be rather a saint, which may indeed be appropriate but is also rather depersonalizing. When I knew him he was just an uncommonly fun friend, part of my inner circle. We hung out, played games, hatched schemes, acted silly.

Does it take adversity of the kind that Jon faced his whole life to make someone passionate, driven, and accomplished? Maybe. I certainly don’t have Jon’s levels of passion, drive, and accomplishment, though I do have some of each. It is very possible that what I do have simply rubbed off of him somehow, long ago.

The circle, already complete, is now illustrated.

Incidentally, that’s Amy Linker in the center of the second row.

Quick thought about creationism and evolution

Let’s see if I’ve got this straight. God:

- can create the heavens and the earth;

- can create every kind of plant and animal;

- can create a man, then take his rib and make it into a woman;

- can get so pissed off at his own creations that he drowns nearly all of them;

- can cause people who formerly shared a common language no longer to understand one another;

- can plant evidence throughout the natural world to mislead us into believing the earth is billions of years old;

- absolutely cannot create an ecological system that continually refines itself through mutation, competition, and heredity.

OK, got it.

Empowered by powerlessness

Yesterday was supposed to be our back-to-school-and-work day after the Christmas holiday and Andrea’s birthday. But Archer was running a fever and it was my turn to stay home with him. Then Andrea talked me into letting Jonah stay home too to “take care of his brother.” No problem, I thought; I’ll let the kids watch a movie and get a little work done. After the long weekend I had a lot hanging over my head.

Then the power went out. And Andrea went to work.

Yesterday was memorably windy here in the Bay Area and we were among the many affected by downed power lines. After scurrying around to perform clean shutdowns of our computers before the UPS’s gave out, we settled in to wait for the power to come back. Power failures are not all that uncommon in our area but they seldom last for more than a few minutes.

Minutes became an hour. The wind outside continued to howl, and our drafty house began to cool. The kids needed some breakfast and I was loath to open the refrigerator, lest our food begin to spoil if the outage was to be a protracted one. But I got the kids fed with a minimum of precious refrigerator-air lost. Then we sat down and began reading books together. I promised the kids a movie as soon as the electricity came back on.

An hour became two, then three. Alex needed a walk, and we had the opposite of the refrigerator problem: I didn’t want to let any of our warm air out. With some deftness I got her outside, then back in, about as quickly as could be managed with a frail, elderly dog.

By lunchtime the power was still out and I called out for pizza. We played with new Christmas toys and read more books. I taught the kids how to play “20 Questions.” Archer, only two and a half, was unclear on the concept: each time it was his turn to think of something he would begin by saying, “Is it an elephant?”

As the hours continued going by and the house continued to cool, I texted with Andrea on my Hiptop. Should we spend the night in a hotel (rather than keep Archer with his fever in a fifty-degree house overnight)? No: we found out that the estimated repair time for our power lines was 5-7pm.

Night came. We lit some candles and carried a flashlight. We hung out under the covers in “the big bed.” 7pm came and went with no electricity. We read more books. I recited the plots of some favorite movies. Andrea came home. The kids ate snacks, then fell asleep. We learned that the repair estimate was for 5-7pm the next day, but chose to stay the night anyway. It was warm enough under the covers, and the house — indeed the whole neighborhood — was delightfully silent. I snuggled under a fleecy blanket in the living room with volume three of The Baroque Cycle and my LightWedge.

At 10:30pm the electricity came back on. Although we had switched off all lights, etc., I knew immediately when power was restored: the total quiet was replaced by faint buzzing and humming coming from every direction as nominally “silent” electronics came to life all at once.

I modestly consider yesterday to have been a parenting triumph. Although Jonah complained, “It’s boring without TV,” in fact that was just a passing sentiment; he was never actually bored. We effortlessly filled an entire day with talking, reading, and interactive play, to say nothing of smiling and laughing, even in the absence of many of our usual comforts — evidence to me of a well-laid foundation for a healthy, fun family.

Happy birthday Andrea!

Today is Andrea’s birthday. She just hates having a birthday on the day after Christmas. For years we have talked about switching to celebrating her half-birthday on June 26th. Perhaps we will start in 2007. Meanwhile, today is her day and I await her birthday decrees.

Santa versus the bees!

One afternoon this past summer I was in my office when the phone rang. It was Andrea. “There are bees in our house,” she told me.

“What?” I thoughtfully probed.

“There are thirty or forty honeybees flying around in the living room. Some of them are starting to die, they’re lying on the floor.”

“Did one of us leave a window open this morning?”

“Nope.”

“Then where did they come from?”

“I have no idea.”

Thus began the Night of a Million Bees. Actually it was only thirty or forty, but to me it seemed like a million. You see, even though as a scientist I like and admire bees, and can even enjoy watching their industrious activities from a safe remove, in person I’m terrified of them. My parents used to make fun of the way I skedaddled out of the way whenever I saw one as a kid; they called it “The Glickstein Shuffle.” In summer camp I was always relegated to right field when we played softball, where the clover was dense and the honeybees were busy. Many were the times when a fly ball would land just a few steps from me while I was preoccupied with staying out of the bees’ way.

Thus began the Night of a Million Bees. Actually it was only thirty or forty, but to me it seemed like a million. You see, even though as a scientist I like and admire bees, and can even enjoy watching their industrious activities from a safe remove, in person I’m terrified of them. My parents used to make fun of the way I skedaddled out of the way whenever I saw one as a kid; they called it “The Glickstein Shuffle.” In summer camp I was always relegated to right field when we played softball, where the clover was dense and the honeybees were busy. Many were the times when a fly ball would land just a few steps from me while I was preoccupied with staying out of the bees’ way.

But now I am the head of a family and I have to be Brave, so I told Andrea to take Alex (our dog), pick up the kids at preschool, and keep them all at her office for the time being. I would go home, scope out the bee situation, and take appropriate action. I fully expected to take one quick look inside, see a buzzing swarm centered over our sofa, say, “Uh huh,” close the door again and get a hotel for a few days while armor-suited professionals tented our house and fumigated the hell out of it.

In fact what happened was this: I went into the house and immediately saw three or four bees on the floor in the entryway, motionless. I crept slowly inside, taking great care with each step, touching nothing and thoroughly scanning the next patch of floor before placing my foot on it. Sweating bullets, heart pounding, I switched on every light in the place until it was ablaze with brilliance, and then got a flashlight for good measure, and a long stick. I found more motionless bees: some in the kitchen sink; some on the sofa; some on the windowsill. I grew a bit bolder and pushed apart the slats of our vertical blinds with my long stick, and shone the flashlight in. There I found more bees. And more still between the sofa cushion, and under the piano bench, etc. Some were quite hard to see.

Then I noticed that a few were moving sluggishly; the first couple I’d seen, in the entryway, seemed to be coming quickly back to life! I trapped them under drinking glasses. Then, still trembling with fear, I plugged in the vacuum cleaner, assembled the long-reach hose, and began sucking up the bees. After ten heart-stopping minutes I believed I’d gotten them all, and only switched off the vacuum after considerable hesitation, certain that when the suction abated they’d emerge all abuzz to exact their revenge.

We slept at home that night, albeit a bit uneasily. But for several days there were no more bees. Then one day we saw three new bees in the living room, flying around, not yet exhausted. Emboldened by my prior experience, I sucked them up with the vacuum cleaner right out of midair. But the mystery of where they could be coming from remained.

One afternoon I heard a strange hum in the living room but saw no bees. I triangulated the sound to — our fireplace! That’s when I noticed that, though our fireplace doors have been closed for years — we never use it — a tiny air vent in the corner of those doors, big enough for a bee to crawl through, had been open all along. I closed it.

Our hypothesis now is that there is a nest of honeybees in our chimney, and perhaps a piece broke off and fell into our flue or even the fireplace. In the confusion some bees escaped through the air vent into our living room. We made a note to address the problem sooner or later, but it drifted down to the bottom of our priority list. After all, closing the vent seemed to solve the problem once and for all, why not let the bees be? We never use the chimney ourselves. We never even open the fireplace.

Except for tonight. Christmas Eve. How will Santa get in?

Tonight the kids will expect us to throw the fireplace doors wide and set out a folding table next to them with cookies and milk for Santa. But there is no way I’m opening those doors. What can we tell the kids to allay their fears that Santa will be locked out?

I may have to haul out the ladder, write a note, and let the kids see me taping it to the roof. “Dear Santa, there are bees in the chimney, please use the patio door.” Then of course we’d have to leave the patio door open, which exposes us to the possibility of a visit by one of the many neighborhood skunks. Bees, or skunks? Either way, Merry Christmas.