Just now, however, I was moved to post the comment “Wow wow wow wow wow” after reading the post John Edwards and The Best Christmas Gift Ever by someone called “leisure.” I hope you’ll read it too. Your heart will grow three sizes.

Author: bobg

It’s the most wonderful time of the year

You better not pout

You better not cry

Your tears might confuse its

Robotic eye

Santatron is coming to town

The first Santa Claus’s

Body’s long gone

The new metal one will

Last an eon

Santatron is coming to town

It knows when you are sleeping

It reads what’s in your head

Its detecting network’s sensitive

From UV through infrared

Its thirty-two limbs

Are state-of-the-art

Its thorax holds Santa’s

Still-beating heart

Santatron is coming to town

(Previously.)

If ghosts could vote

In my mom’s case, her doctors wanted to keep her at the hospital while she recovered from a severe infection and received radiation treatments for (a very treatable form of) cancer. The insurance company said no and sent her to a nursing home, where the standard of care was far lower. There her health declined rapidly; she was dead within a few weeks.

Now here’s a surprising fact: of the 100 U.S. Senators, Democratic and Republican, who is the one who has taken the most campaign money from evil HMO’s? Hillary Clinton.

Here is another surprising fact: who is the U.S. Senator who has taken the second largest amount of HMO money? Barack Obama.

Now, which presidential candidate made a career of fighting evil HMO’s and drug companies and their ilk — and winning? Which one has promised, if elected, to discontinue Congress’ golden health-care plan unless it passes meaningful health-care reform? Which one has a detailed and realistic plan for just such reform? And which one has opted for public campaign financing in order to be free of undue corporate influence? John Edwards.

My mom’s ghost and I implore you to vote for John Edwards. He’s our only good hope for making sure the insurance companies don’t turn too many other people into ghosts.

Lightsaber duels: who wins?

Luke: Is the dark side stronger?

Yoda: No, no.

Let’s examine the evidence, shall we? Remember: anger, fear, aggression — the dark side are they.

This chart considers duels only between Force-adept antagonists (which eliminates the battle between Obi-Wan Kenobi and General Grievous).

| Star Wars | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Good guy | Bad guy | Winner | |

| Obi-Wan Kenobi | Darth Vader | The bad guy | |

| The Empire Strikes Back | |||

| Good guy | Bad guy | Winner | |

| Luke Skywalker | Darth Vader | The bad guy | |

| Return of the Jedi | |||

| Good guy | Bad guy | Winner | But |

| Luke Skywalker | Darth Vader | The good guy | In a fit of rage! |

| The Phantom Menace | |||

| Good guy | Bad guy | Winner | But |

| Qui-Gon Jinn | Darth Maul | Stalemate | Darth Maul appeared to have the upper hand before Qui-Gon was whisked away. |

| Qui-Gon Jinn | Darth Maul | The bad guy | |

| Obi-Wan Kenobi | Darth Maul | The good guy | In a fit of rage! |

| Attack of the Clones | |||

| Good guy | Bad guy | Winner | |

| Obi-Wan Kenobi, Anakin Skywalker, and Yoda | Count Dooku | The bad guy | |

| Revenge of the Sith | |||

| Good guy | Bad guy | Winner | But |

| Mace Windu | Palpatine | The good guy | Not for long |

| Hordes of Jedi “younglings” | Darth Vader | The bad guy | |

| Yoda | Palpatine | The bad guy | Yoda would have won… if he hadn’t simply left. WTF?! |

| Obi-Wan Kenobi | Darth Vader | The good guy | How good is a “good guy” who leaves his mutilated, helpless one-time friend to die in agony? |

The record is not too favorable for the good guys. In fact it looks like the only good guy who wins while acting like a good guy is Mace Windu! You see, this cat Mace is a baaaad mother– Shut yo mouth! But I’m talkin’ ’bout Mace! Then we can dig it.

The record is not too favorable for the good guys. In fact it looks like the only good guy who wins while acting like a good guy is Mace Windu! You see, this cat Mace is a baaaad mother– Shut yo mouth! But I’m talkin’ ’bout Mace! Then we can dig it.

Happily, my son Jonah bucked the odds recently when he battled Darth Maul to a draw under the guidance of his teacher, Jedi Knight Tiere Kai, when the Sith Lord paid a surprise visit to Jedi Training Academy.

Humbled by Henson

This short avant garde film provoked three very strong reactions from me: (1) No amount of adulation or awe of Jim Henson is too much; (2) I’m sorry I missed the Sixties; and (3) Frank Oznowicz?!

My five-year mission

Twenty years ago my first serious professional programming gig began, helping to maintain and develop features for “Andrew,” the campus computing environment in use at Carnegie Mellon University. The technology in Andrew was ahead of its time. My specialization was in the e-mail components of Andrew, and it launched me on a mostly rewarding career of mostly e-mail software development.

My years working on the Andrew project were golden. Part of this is due to the effect of nostalgia, of course; another part is due to the novelty of a regular paycheck; still another, the outstanding colleagues from whom I learned so much. But a big part of what I loved about that job was being able to perceive the effects of my work on my user base, for better or worse, which not all software engineers are able to do. When we rolled out a new feature that I had worked on, the campus message boards would immediately light up with excitement about it. When e-mail wasn’t working well, the frustration emanating from all corners of the university was palpable in my office. And if I was then able to fix it — especially if it involved clever detective work — that was my idea of heaven.

(On one memorable occasion, I unadvisedly rolled out a version of the mail system on my own to the whole campus late at night, thinking to fix a small bug; instead I broke mail for everyone. Frantically I tried to fix things until I realized I couldn’t without help, and that help wouldn’t arrive until early the next morning. The thought that mail wasn’t working for anyone at CMU that night tormented me so that I went to a local bar to drown my sorrows. A cute waitress there who was an acquaintance of mine listened to my story and sympathized with me. “And today that woman is my wife.”)

Five-year trophy

This is the fifth anniversary of my joining Danger, Inc., a cool company with cool people, products, and services. A big part of what I love about this job is that it recaptures a lot of what I loved about the old CMU job: once again I am overseeing a high-volume, advanced-technology e-mail service used by a very large number of people all the time, and once again I have the occasional pleasure of hunting down and solving serious software bugs and making life better for everyone at once.

On this particular day, though, as I recuperate from a week of pneumonia, what I’m most grateful for is Danger’s health insurance plan… and my fleecy, unreasonably comforting “Danger” hoodie, without which recovery would have been nigh impossible.

Pneumonia?!

I always thought pneumonia was something you got only if you didn’t take proper care of a cold. But as I learned today, you can go from healthy straight to pneumonia. That explains the past week’s worth of fever, cough, and weakness.

Seriously, 2007, you are starting to piss me off.

Censure Dianne Feinstein

For years I have been sending letters to Senator Dianne Feinstein expressing disappointment in one vote of hers or another. She is on the wrong side of many issues.

In the recent past she has outdone herself in coddling the Bush administration. She helped Michael Mukasey become Attorney General — the top law-enforcement officer of the nation — despite his refusal to renounce torture, an illegal practice. And she has voiced her support of “telecom immunity,” which would rescind privacy laws that telecom companies broke, for no reason other than that the burden of defending themselves in the resulting lawsuits is too onerous. (Message: break any laws you want if you can pay later to have it officially overlooked.)

These actions were taken under a serious conflict-of-interest cloud. Feinstein’s husband, Richard Blum, is a defense contractor whose company has won lucrative no-bid contracts from the Bush administration.

Every time I’ve mailed her an objection, I’ve received a prompt, polite, and discursive response telling me we’ll just have to “agree to disagree.” Enough of that.

So I’ve joined the Courage Campaign’s effort to have the California Democratic Party censure her. Please do the same.

I also plan to send her a small bottle of cheap perfume with the note, “You stink.”

The beginning of wisdom

[This post is participating in Strange Culture’s Film + Faith Blog-a-thon. Warning: spoilers follow for the book and film Contact. Update 16 Dec: this post is also participating in Joel Schlosberg’s second annual Carl Sagan Memorial Blog-a-thon.]

I read Carl Sagan‘s novel, Contact, soon after it was published in the late 1980’s, and enjoyed it greatly. It’s the story of a radio astronomer, Ellie Arroway, who is the first person on Earth to detect, verify, and begin deciphering a genuine extraterrestrial message.

A considerable part of the story is devoted to the societal implications of Arroway’s discovery, especially among various religious communities. As it’s depicted in the book, Ellie must suffer various crackpots, blowhards, and garden-variety religious leaders (well-meaning but deluded) spouting their superstitious blather in her quest to secure the resources needed to finish decoding the alien transmission and build the Great Machine.

For the transmission includes, among other things, construction plans for a tremendous and tremendously complicated machine. At its center is a capsule that seats five intrepid adventurers. No one knows what will happen when the machine is switched on. Will the capsule launch into space? Travel through time? Pop into a different dimension? Or is it a weapon that will obliterate the Earth?

The trials involved in achieving the goal of building and activating the Machine are portrayed very much as the power of pure reason overcoming the fetters of fear and ignorance. In the end, Ellie and her fellow travelers are propelled across vast distances and have a surprising encounter with a superior but benevolent race. When they return days later, they discover that no time has elapsed on Earth, leaving a diehard core of doubters free to insist that nothing at all happened, even though there is compelling evidence to support the stories told by Ellie and the others. Science is the clear winner, religion the loser, and it’s pure wish fulfillment: what atheist hasn’t dreamed of winning one of those unwinnable arguments about faith and science against a true believer?

In Robert Zemeckis’ film version of Contact, things are subtly different. Ellie is as much an empiricist as in the book, but man-of-God Palmer Joss is much less easy to dismiss out of hand. His interplay with Ellie on the subject of faith leaves her uncharacteristically at a loss, unable to turn him aside by articulating the bedrock principles of skeptical inquiry.

When the time comes to try the Machine, crucially there is room in it for only one person, so that when Ellie returns from her amazing journey there is no one to corroborate her account. There is also a total absence of physical evidence to support her story. Ellie ends up passionately, desperately trying to persuade people to believe what she is certain is true but cannot prove. Palmer Joss sympathetically points out that this is precisely the situation in which persons of faith find themselves.

It’s a marvelous storytelling contrivance, and the dialogue and performances drive the point home economically and convincingly. But I left the theater conflicted. On the one hand, the film had excellent performances and astonishing visuals, it was exhilarating to see an intelligent, uncliched portrayal of science and scientists in a mainstream Hollywood movie, and it was in many respects faithful to the novel. Where changes were made, by and large they were to add some emotional depth that had been missing from Sagan’s plot- and technology-heavy writing. On the other hand, the rebalancing of science and religion changed what the story was fundamentally about! It offended me that Carl Sagan, recently deceased after a lifetime of science advocacy (today would have been his 73rd birthday, by the way), should have his fantasy about the triumph of humanism and reason watered down for a mass audience!

Over time, though, the film version grew on me and I recognized it as something greater than the source novel: an adventure in which reason triumphs and an exploration of the tangled interrelationship between belief and skepticism. Where I had been hoping to see religious moviegoers get schooled in the virtues of rational thought, instead I had received a lesson about the nuances and complexities of the human experience. The science-beats-religion version of the story had become, to me, overly simplistic. (Sorry, Carl.)

After all, even Mr. Spock admits, near the end of a long career working with humans, that “logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end.”

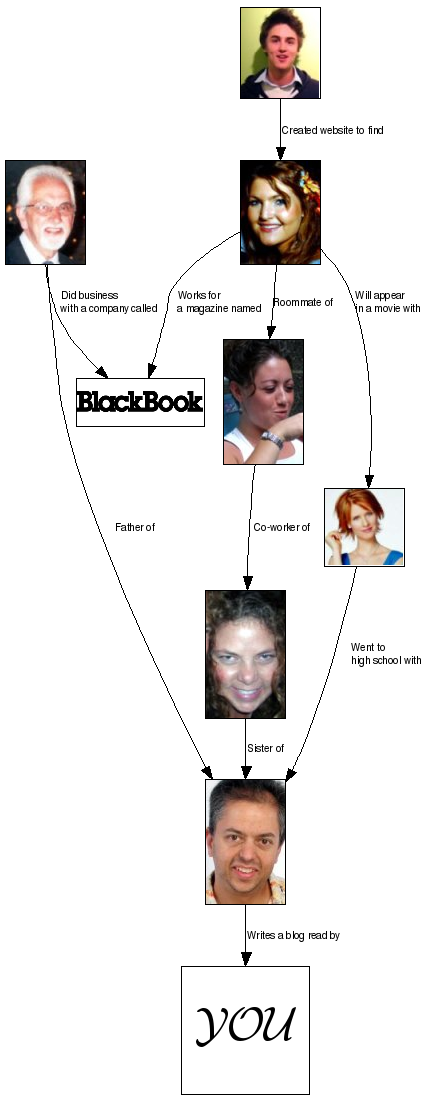

It’s all about you

The NYGirlOfMyDreams story? Thanks to me, it’s all about you.