I was going to write about the ending to The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, but Maul of America beat me to it.

So then I started thinking about other movies whose ending pays us off with a memorable, wordless facial expression like that one does (making this a sort of companion piece to my earlier post, “When words meet faces“). Warning: spoilers ahead.

The first movie like this that came to mind was Monsters, Inc. In that film, it is the job of monsters from the “monster world” to enter children’s bedrooms in the human world each night through magic doors and scare them into producing screams, which the monster world harvests for its energy. Secretly, monsters are terrified of children. One night, despite elaborate precautions, an adorable little toddler escapes into the monster world and is discovered by Sully, the champion scarer at Monsters, Inc. At first Sully is frightened of her but she soons endears herself to him. After a game of peek-a-boo, he decides to call her “Boo.” (Sully’s friend Mike is alarmed. “You’re not supposed to name it! Once you name it, you start getting attached to it!”) Amidst Boo’s pre-verbal babbling she calls him “Kitty.” He becomes protective of her and determines to return her to her bedroom, but machinations at Monsters, Inc. make this a challenge, and an adventure ensues. In the end, after helping to expose an evil plan, jail some criminals, and transform Monsters, Inc. from harvesting children’s screams to using their laughter, Sully finally bids Boo an emotional farewell and sends her back to her bedroom. Her door is put through a door-shredder.

Some time passes. Monsters, Inc. is doing better than ever now that it’s harvesting laughs instead of screams, but Sully misses Boo. One day, Sully’s friend Mike gives him a gift: Boo’s door, painstakingly reassembled from its shredded wooden fragments. Sully opens the door and tentatively peers through it. “Boo?” A more grown-up voice answers, “Kitty!” Sully’s face registers first surprise and then the most satisfying smile of delight ever animated.

While thinking about this post, my kids watched Spider-Man 2 on DVD and I was reminded of its ending, which is also a memorable, wordless facial expression.

Peter Parker has loved Mary Jane Watson all his life, but after the events of the first Spider-Man film he realized he must not place her in danger by letting anyone know he loves her; so he rejects her. In the next film, she reluctantly becomes engaged to another man. But the events of the film lead to her discovering Spider-Man’s true identity and the real reason for Peter’s rejection; he does in fact love her. She leaves her fiancé at the altar, runs to Peter’s side, and declares her love and her intention to face danger with him. “Isn’t it time someone saved your life?”

A moment later, they hear police sirens from the street below. MJ lets Peter go catch more bad guys. He leaps from his window as Spider-Man, exultantly swinging through the concrete canyons of Manhattan. He has reconciled his personal life with his responsibilities as a superhero, which has been the “through-line” of the film.

But interestingly, the movie doesn’t end there. It shifts into a more downbeat finale, cutting back to a rueful MJ as she stands in Peter’s window, watching him recede into the distance and fretting about the future.

A similar but much more classic “what have I gotten myself into” ending is in The Godfather. Michael Corleone has consolidated the power of the Corleone crime family, but his wife Kay has misgivings about the man he’s becoming. She confronts him in his office about his role in the disappearance of Carlo, his brother-in-law. “Don’t ask me about my business, Kay,” Michael warns, but Kay persists, angering him.

In the world of The Godfather, women don’t matter, except in how they can be used. So it takes no effort for Michael to pretend magnanimity and lie to his wife. “Alright. This one time. This one time I’ll let you ask about my affairs.” He gives a neat and tidy answer that sets her mind at ease. As she moves to the adjoining room to fix them both a drink, some of Michael’s lieutenants arrive in his office, one of them perfunctorily closing the door on Kay, whose face shows surprise and hurt. It’s man-talk and she can never be a part of it. And catching this glimpse of Michael about to do business, she wonders if she can believe what he just told her — or indeed anything at all.

But as classic as The Godfather is, the granddaddy of rueful ambivalence is the ending of The Graduate. Benjamin Braddock, having let grownups heave him from one situation to another his whole life, has finally seized control of things himself. Overcoming many obstacles he hurries to the chapel where Elaine Robinson is about to marry another man. “Elaine! Elaine!” he shouts to her through a glass wall.

After a melee he succeeds in extracting her from the ceremony, eluding an angry mob of family and wedding guests, and herding Elaine onto a city bus, where their initial excitement at being reunited and avoiding an unwanted marriage turns to disquiet: Elaine remembering what a cad she found Benjamin to be only a short time ago; Benjamin remembering that it was not his own idea to call on Elaine in the first place, but that of another grownup. Will he ever be his own man?

Fortunately, no one was hurt. A short time later, Sir Topham Hatt arrived. He was very cross. “[Engine X], you were not paying attention. You have caused confusion and delay. I have asked [Engine Y] to take your place. You must go back to the shed for repairs.”

Fortunately, no one was hurt. A short time later, Sir Topham Hatt arrived. He was very cross. “[Engine X], you were not paying attention. You have caused confusion and delay. I have asked [Engine Y] to take your place. You must go back to the shed for repairs.”

Chuck, apparently interpreting this to mean “race-appropriate,” indelicately suggested, “We do know the theme song from

Chuck, apparently interpreting this to mean “race-appropriate,” indelicately suggested, “We do know the theme song from  After the Chud cards were distributed, Steve announced that the winner would receive a prize. The prize was beef jerky. A few days earlier, Andrew and I had gone to a snack-food wholesaler to buy enough beef jerky for the whole audience.

After the Chud cards were distributed, Steve announced that the winner would receive a prize. The prize was beef jerky. A few days earlier, Andrew and I had gone to a snack-food wholesaler to buy enough beef jerky for the whole audience.

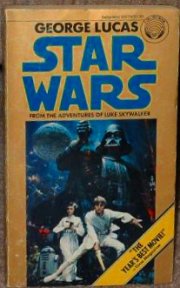

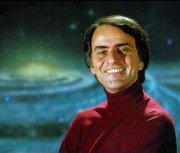

Sagan’s famous Tonight Show appearances happened right around the time I was old enough to stay up and see them. Early on I remember being annoyed by his criticisms of Star Wars (to wit: that spaceships don’t make whooshing noises in space, that Chewbacca deserved a medal at the end too, etc). But then my mom, who I think had a bit of a crush on him, urged me to read

Sagan’s famous Tonight Show appearances happened right around the time I was old enough to stay up and see them. Early on I remember being annoyed by his criticisms of Star Wars (to wit: that spaceships don’t make whooshing noises in space, that Chewbacca deserved a medal at the end too, etc). But then my mom, who I think had a bit of a crush on him, urged me to read