[This post is participating in Cerebral Mastication’s

Indiana Jones blog-a-thon.]

Speaking of subtle filmmaking techniques…

The rousing musical score that John Williams wrote for Raiders of the Lost Ark included several melodic themes: two for Indiana Jones and one for Marion, a motif for the German army, and of course a theme for the lost ark itself, suitably spooky. As an avid fan of the film and of John Williams I’ve listened to the score countless times over the past 27 years. But as a musical layman, it wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I noticed something clever that John Williams seemed to be doing with the Ark Theme.

We hear the Ark Theme for the first time when Indiana Jones shows an illustration of the ark to the Army intelligence men who come to meet him.

As you can perhaps hear in that clip, the melody doesn’t quite resolve; it segues into a few notes’ worth of Indy’s theme (a.k.a. “The Raiders March”). But the Ark’s theme is heard again just a few moments later when Marcus expresses his misgivings about this assignment to Indy.

In this clip, Indy starts out thinking about his old flame — “Suppose she’ll still be with him?” — and Marion’s theme plays for a few bars, but then Marcus tells him, “For nearly three thousand years, man has been searching for the lost ark,” at which point the Ark Theme comes in. But once again it does not resolve, segueing this time into the flying-boat travel montage.

The next time the Ark Theme appears, Indy is in the Map Room. This scene is divided into four sequences, each of which includes a rendition of the Ark Theme, each separated from the others by a cut to Indy’s friend Sallah, who’s waiting for him outside.

In the first Map Room sequence, Indy lowers himself by rope into the room and looks at the miniature city on the floor. The Ark Theme plays almost to completion, but leaves off the final note when cutting to Sallah being harassed by some German soldiers.

Next Indy deciphers some hieroglyphics and checks the position of the sun. The Ark Theme plays barely halfway through this time.

Now Indy affixes the medallion to the Staff of Ra, places the staff in the proper hole, and fervidly awaits the proper alignment of the sun. At last the angle is right and a brilliant beam of light reveals the location of the Well of the Souls! The music reaches a crescendo and a satisfying resolution — but while Indy was waiting for the sunlight to creep across the Map Room floor, the melody modulated into another key. We still have not heard the Ark Theme play from beginning to end!

In the coda to the Map Room scene, Indy snaps the Staff of Ra in two and looks for his rope to climb out, but it’s missing. Sallah drops an improvised replacement into the hole. The Ark Theme peters out on a visual gag: Indy discovering a Nazi flag knotted into his makeshift rope.

In the very next scene, Indy, disguised (poorly) as an Arab, ducks hastily out of sight when some soldiers approach too closely. He enters a tent and discovers, tied to a tent pole, Marion — who he thought had been killed! He’s about to free her when he realizes he can’t without raising an alarm. Marion wonders why he’s not cutting her bonds. He tells her, “I know where the ark is, Marion,” and we hear the Ark Theme again. As he explains and she becomes frantic, the music segues into Marion’s theme.

Next, Indy uses a surveying instrument to convert his Map Room calculations into an actual location for digging. A variation on the Ark Theme plays, still unresolved.

A short time later, Indy arrives at his calculated location with a team of diggers. He clambers up a rise alone, scopes it out, and calls his team over. The first half of the Ark Theme plays three times in slightly different forms, and there’s a crescendo as Indy removes the first shovelful of sand, but it’s still not a resolution of the complete Ark Theme.

We get a few notes of the Ark Theme again (listen closely) as Indy and Sallah heave the stone cover off the chest protecting the ark…

…and then a few more as they lift the ark out of its container…

…and another few when Belloq spots the illicit dig early in the morning (“Colonel, wake your men!”)…

…and then once more as German soldiers converge on Indy’s dig site. Once again the final resolving note is left off.

The next appearance of the Ark Theme comes much later. The main characters are now all on a secret Nazi island submarine base. The Ark Theme accompanies the procession of Belloq, Marion, a lot of Germans, and the ark itself (and secretly Indy too) across the island to the ceremonial altar. It’s interrupted when Indy steps out of hiding and levels a bazooka at the group.

Indy’s bluff is called, and he’s captured and brought to the altar to witness the opening of the ark. Belloq mutters some sacred words in Aramaic, the ark is opened — and the stone tablets are not inside, just a bunch of sand. (Psych!) Disappointment turns to bewilderment, though, as the electrical equipment shorts out and an eerie fog spills out of the ark. Here’s the Ark Theme again. This time, just before it resolves it gives way to a danse-macabre version of itself.

That version also doesn’t resolve. Instead it becomes a staccato nightmare as the power of the ark is unleashed.

Finally, the one and only time in the whole film that the Ark Theme is heard from beginning to end, complete with a melodic resolution in the same key, comes as the ark purifies the island by fire, then seals itself back up.

The long-awaited resolution of the Ark Theme creates a sensation of finality. The music subconsciously reinforces the action on the screen: hearing the melody conclude at last, there can be no question that that’s all we’ll see or hear from the ark. Not even the film’s final scene, in which the ark is packed away in a crate inside a gigantic warehouse, repeats the resolution.

Now let’s see if the new sequel betrays that satisfying sense of finality by “going back to the well,” as it were (the Well of Souls!) and unearthing the ark again.

Inevitably Andrea raised the question, “Did that guy ever do anything else?” referring to Paul Freeman, the actor who turned in a memorable performance as Belloq, Indy’s Nazi-collaborating rival.

Inevitably Andrea raised the question, “Did that guy ever do anything else?” referring to Paul Freeman, the actor who turned in a memorable performance as Belloq, Indy’s Nazi-collaborating rival. A few months before that, New York magazine published an article about our school called “

A few months before that, New York magazine published an article about our school called “ Anyway, when I passed that importer’s storefront two years later — with the opening of the first Indiana Jones sequel just a few days away — and my eyes alighted on bagsful of six-foot-long imitation-leather bullwhips for a dollar apiece, I snatched up several dozen.

Anyway, when I passed that importer’s storefront two years later — with the opening of the first Indiana Jones sequel just a few days away — and my eyes alighted on bagsful of six-foot-long imitation-leather bullwhips for a dollar apiece, I snatched up several dozen.

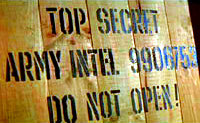

Only look: the number on the crate in the new picture is 9906573. Could I have been the only one to notice immediately that this does not match the number on the crate in the first film, 9906753?

Only look: the number on the crate in the new picture is 9906573. Could I have been the only one to notice immediately that this does not match the number on the crate in the first film, 9906753? Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen.

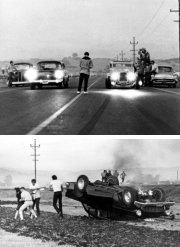

Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen. This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process.

This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process. Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away.

Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away. Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction.

Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction. Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947.

Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947. Both movies revolve around a gold medallion with extraordinary properties, and:

Both movies revolve around a gold medallion with extraordinary properties, and: