In which the author evades a citywide pursuit, battles a gang of ruffians, and kisses two women within minutes of each other.

From seventh through twelfth grades I attended Hunter College High School in Manhattan. I took the subway from Queens in the morning and back again to Queens after school. Most days I rode home with my friend and fellow Queens resident Chuck.

We were two geeky little guys, and we had female counterparts at Hunter: Kathy and Joelle.

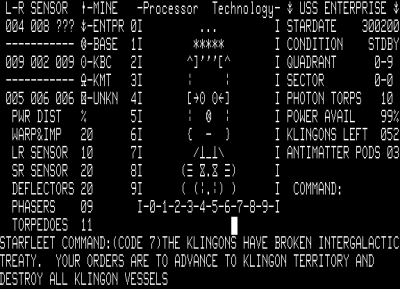

They were the sort of girls who were into Tarot and Stevie Nicks and Lord of the Rings and guys who played Dungeons and Dragons. By rights, Chuck and I should have been D&D players, considering our other interests such as computers, electronics, and Star Trek; but we weren’t. That didn’t keep Kathy and Joelle from acting interested in us, though; and being still at the dipping-pigtails-into-inkwells stage of relating to women, Chuck and I feigned displeasure at Kathy’s and Joelle’s attentions.

(Not that they were especially mature themselves. Their nicknames for me and Chuck were “Cow-face” and “Moose-face,” respectively, and they delighted in pretending to annoy us.)

As it happened, Kathy and Joelle also both lived in Queens and so we frequently encountered one another en route in the afternoons. (Somehow none of us ever ran into one another in the mornings.) Whenever this happened, Chuck and I always made a big show of being vexed, and Kathy and Joelle always made a big show of following us as we tried to evade them by switching trains, walking to the far end of the platform, etc.

Of course, it was love, but none of us ever figured that out.

One time, for no particular reason, the chase was truly on. Kathy and Joelle made clear that they’d stick to us like glue on the ride home that day, so the instant school let out, Chuck and I raced for the 96th Street station and counted ourselves lucky to get on a number 6 train almost immediately, before the girls could catch up. At 59th Street we got off the 6 to switch to the N train — and there we found Kathy and Joelle waiting for us! When they saw us run from the school, they knew they’d never catch us if they followed us to the 96th Street station, so they hot-footed it down to 86th Street, where they caught the 4 express and beat us to 59th Street!

You can’t go home again

The N train no longer goes where it used to. The RR train no longer even exists. The one constant in the New York subway is change. Change, and the smell of stale urine. Two! Two constants. Here is what the MTA route system looked like around the time of this story; here is what it looks like today.

Chuck had a plan. On his cue, we unexpectedly hopped onto a departing RR train after its doors had closed (using the cool but stupidly dangerous leap-on-between-cars maneuver), leaving Kathy and Joelle behind once again. At Queensboro Plaza we switched to the 7 train, and got off at Roosevelt Avenue to transfer back onto one of the Queens Boulevard trains.

And there were the girls again, waiting for us with shit-eating grins, having foreseen our strategy. We conceded the battle and rode home the rest of the way with them.

One other time, perhaps a year later, I was waiting on the Queens Plaza platform after school with Joelle, maybe Kathy, maybe Chuck, and maybe one or two other Queens friends, when a group of slightly older kids started verbally taunting us. Naturally we ignored them. Then they began to insult the girls. I got angry and said something to them in the way of a warning, I don’t remember exactly what; then we continued trying to ignore them. The last straw for me was when their harassment became physical, to wit: tapping some of us on the head. I felt protective of my friends and grew uncharacteristically bold. I threw down my knapsack and demanded we be left alone. “What are you gonna do about it?” asked the chief bully, and gave me a shove. I shoved back and the fight was on. We circled each other with our fists up, each of us swinging occasionally and either missing or landing pretty ineffectual blows.

[I am a lover, not a fighter, but I am not above settling the hash of someone deserving. Though I don’t remember it, my mom loves to tell the story of the time I finally snapped and beat the crap out of my elementary school’s resident bully — who treated me as a friend ever after.]

The fight somehow petered out with no resolution. When a train came, his group and mine got on separate cars. It was one of the newer R-46 trains that prevented crossing from one car to the next without an operator’s key, so once we were underway, that was pretty much the end of that.

Through the window to the next car we saw the gang get off at the next stop, Roosevelt Avenue. However, as the conductor announced, “Watch the closing doors” and the door-warning chime went “ding dong,” the bully I’d fought ran back onto my train car, punched me square in the nose (knocking my head back into the wall behind my seat), and hopped back off.

I saw stars. But nothing was broken or bleeding, I had the sympathy and admiration of my friends, and the bully’s cowardly final act had given me a moral victory that I still savor.

There’s a nice little coda to the Bob-Chuck-Kathy-Joelle story in which I get kisses from both women.

In our senior year at Hunter, we had our Spring Carnival in the schoolyard. Kathy was one of a few people manning (“womanning”?) the kissing booth, and for a buck I finally got a smooch from her.

Another booth was a dunk tank — one dollar for one throw of a baseball at a target that would drop some poor sap into a tank of water. To my great surprise, there was Chuck, sitting on the hot seat in a bathing suit and T-shirt, looking distinctly dry. “I’ve got to try this,” I said, as I handed a dollar over to the booth barker — Joelle. Now, Chuck, Joelle, and everybody else in the world knew that I was athletically — what’s the right word? — pathetic. A small crowd gathered of folks who knew this fact and the fact that Chuck and I were best friends. Chuck taunted me confidently from his perch. I wound up and hurled a true baseball-style pitch. On that sunny afternoon the gods of great story endings guided my throw straight and true. The ball struck, a bell rang, and the look of astonishment on Chuck’s face as he fell into the water was worth a million bucks. Joelle squealed, jumped, and gave me a hug and a kiss.

As a junior, late in 1982, a few friends and I felt the urge to write and perform a collection of short one-act plays. With faculty help we ended up founding The Brick Prison Playhouse (so called because the school’s appearance earned it the affectionate nickname “the brick prison”), a repertory group for performing student-written plays, as opposed to the existing repertory groups that performed established plays and musicals.

As a junior, late in 1982, a few friends and I felt the urge to write and perform a collection of short one-act plays. With faculty help we ended up founding The Brick Prison Playhouse (so called because the school’s appearance earned it the affectionate nickname “the brick prison”), a repertory group for performing student-written plays, as opposed to the existing repertory groups that performed established plays and musicals. A few months before that, New York magazine published an article about our school called “

A few months before that, New York magazine published an article about our school called “ Anyway, when I passed that importer’s storefront two years later — with the opening of the first Indiana Jones sequel just a few days away — and my eyes alighted on bagsful of six-foot-long imitation-leather bullwhips for a dollar apiece, I snatched up several dozen.

Anyway, when I passed that importer’s storefront two years later — with the opening of the first Indiana Jones sequel just a few days away — and my eyes alighted on bagsful of six-foot-long imitation-leather bullwhips for a dollar apiece, I snatched up several dozen. But in all it was a lot of fun. The high point was when the manager suggested I climb into the driver’s seat of a gleaming red 308 (oh okay) and handed me the keys… to lower the window. We took a few shots like that, the girls trying to arrange their faces around the window as I gripped the wheel of a Ferrari.

But in all it was a lot of fun. The high point was when the manager suggested I climb into the driver’s seat of a gleaming red 308 (oh okay) and handed me the keys… to lower the window. We took a few shots like that, the girls trying to arrange their faces around the window as I gripped the wheel of a Ferrari.

A few days ago I read

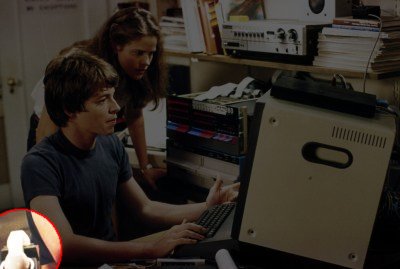

A few days ago I read  my new friend Chuck had a computer at home, which was almost unheard of in those days. (His dad was a professional programmer and weekend computer hobbyist.)

my new friend Chuck had a computer at home, which was almost unheard of in those days. (His dad was a professional programmer and weekend computer hobbyist.) The resulting game, which we called ElectroMusiQuiz, required players to answer music-history questions on cards that could then be inserted into a slot that would cause the right answer to appear on a 7-segment LED. A right answer meant you could advance your gamepiece across the board. ElectroMusiQuiz was extremely crude, but on the day everyone brought in their board games, ours was the one everyone wanted to try!

The resulting game, which we called ElectroMusiQuiz, required players to answer music-history questions on cards that could then be inserted into a slot that would cause the right answer to appear on a 7-segment LED. A right answer meant you could advance your gamepiece across the board. ElectroMusiQuiz was extremely crude, but on the day everyone brought in their board games, ours was the one everyone wanted to try!  (This was before ubiquitous electronic goodies, you must understand, when

(This was before ubiquitous electronic goodies, you must understand, when

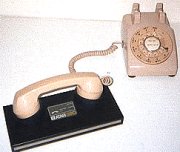

Occasionally we’d watch in awe as Chuck’s dad used a modem to connect his computer to the mainframe at his office. It was an acoustic modem, the kind Matthew Broderick uses in WarGames, where a telephone handset is jammed into a pair of rubber cups, one housing a mic for listening to the screechy data sounds from the handset, and one housing a speaker for making screechy data into the handset’s mic. Such a device was only possible, of course, at a time when telephone handsets were all a standard size and shape.

Occasionally we’d watch in awe as Chuck’s dad used a modem to connect his computer to the mainframe at his office. It was an acoustic modem, the kind Matthew Broderick uses in WarGames, where a telephone handset is jammed into a pair of rubber cups, one housing a mic for listening to the screechy data sounds from the handset, and one housing a speaker for making screechy data into the handset’s mic. Such a device was only possible, of course, at a time when telephone handsets were all a standard size and shape.

I went to elementary school at P.S. 196 in

I went to elementary school at P.S. 196 in  While Amy’s show was on the air, I attended

While Amy’s show was on the air, I attended