I finished disc six just last night and HOLY CRAP! I got it in the mail to Netflix first thing this morning hoping for disc seven to arrive by Wednesday. I logged in to Netflix to see the episode titles on the next disc… and discovered that disc seven is merely the “special features” disc with no new episodes on it. I finished season two without even realizing it, and now I can’t see season three until it comes out on DVD. Bogus!

Author: bobg

Shh

My life has always been noisy. I grew up in an apartment in Queens right under an approach route for LaGuardia Airport. Most days of the week I spend two or more hours commuting in a poorly soundproofed economy car. And of course I am almost continuously sitting at high-powered computers and the constant drone of their cooling fans.

One day I decided to try to find a quiet spot. A really quiet spot, where I could hear no trucks rumbling by, no gas station air compressors, no high school football team; no crashing surf or gurgling brook; preferably not even any wind, or the rush of my own blood in my ears (as when they’re underwater or stuffed with earplugs). I didn’t want to not hear anything; I wanted to hear nothing. I wanted to listen to silence. Obviously no place in or near the Bay Area would suffice, so I located Pine Mountain Lake airport on the San Francisco sectional chart. Of all the places within easy flying distance, Pine Mountain Lake appeared to be the most remote and the most likely to be quiet (once I shut down the Cessna’s engine). My friend Steve came along for the trip. We crammed our bikes into the back of the plane just in case we had to put a little distance between us and the airport in order to find silence. But even on the mountainous roads of Pine Mountain Lake, the whoosh of cars and clatter of trucks are inescapable.

If I were more intrepid and more persistent in this quest I’m sure I would eventually have found something to satisfy me — in the desert, perhaps, or out on a calm sea. But this goal languishes way, way down my priority list. I was glad to see recently that others are more dedicated to the cause, and have been more successful, to wit: One Square Inch of Silence.

Archer 1, parental authority 0

Having lots to catch up on at work, Andrea and I were eager to get the kids off to preschool this morning. But Archer had gotten used to lots of one-on-one parent-child time and was determined to stay home again. He refused to allow me to dress him. I coaxed him gently for a while and promised some fun family activities after school and work, but to no avail. Then I ratcheted up the sternness and started to tell him that certain privileges would be unavailable later if he continued to resist me now. When that didn’t result in improved cooperation, I resorted to, “Do we do this the easy way or the hard way?” The kids know that the hard way is no fun, so this threat almost always works — but not this time.

So, the hard way. I confiscated the items that Archer had been carrying around and pinned him to the changing table while wrestling his pajama top off and then his shirt on over his head. After lots of struggle, and plenty of crying from Archer, I managed to get his clothes on.

My victory was short-lived. Archer still held the trump card — the one sure way to make me remove the clothes I had just forcibly caused him to wear. With an assist from his convulsive crying and a belly full of Malt-O-Meal, he barfed all over them.

My victory was short-lived. Archer still held the trump card — the one sure way to make me remove the clothes I had just forcibly caused him to wear. With an assist from his convulsive crying and a belly full of Malt-O-Meal, he barfed all over them.

A cautionary tale for all who believe their authority is absolute.

That could have been me

People die every day. Plenty of stories are sadder than this one. What makes some grab at the imagination more than others? In this case, for me, the answer was pretty clear (even before I knew about my indirect personal connection to the Kims — they’re close friends of my boss, Matt): James Kim could have been me. He was a middle-class Bay Area computer nerd, intelligent and nice, with a young family that liked to take long car trips.

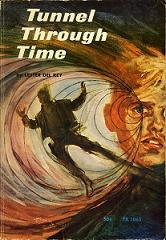

My own experience with being underdressed, underequipped, and disoriented in a snowy wilderness was orders of magnitude more brief and less perilous, but I think it taught me well enough not to strike out across open country under such circumstances. But how long could I resist the temptation to go for help when my family is freezing and starving before my very eyes? Superior, self-appointed survival experts all over the Internet are today pompously pronouncing that James should never have left the car. Easy for them to say. I think he showed more restraint than I would have under similar circumstances by staying with the car for as many days as he did. And after all, there are worse ways to die than by hypothermia  (the end stages of which can be quite misleadingly pleasant — you get warm and drowsy — learned that in fifth grade from Tunnel Through Time by Lester Del Rey) while heroically trying to rescue your wife and children, as half the online world prays for you.

(the end stages of which can be quite misleadingly pleasant — you get warm and drowsy — learned that in fifth grade from Tunnel Through Time by Lester Del Rey) while heroically trying to rescue your wife and children, as half the online world prays for you.

Reportedly, the Kims took an ill-chosen alternate route to get from Interstate 5 inland to US-101 on the coast. How many times have Andrea and I spotted a more-interesting looking road on the map and said, “Let’s have an adventure!” (We did it on this road once near Half Moon Bay and almost had a wilderness crisis of our own — on dry roads, near the heart of the Bay Area — when we nearly ran out of gas as night fell.)

Having grown up on the East Coast, I know how treacherous even slightly hilly, slightly curvy secondary roads can be in the snow, so I think I’d know better than the Kims did about choosing that winding mountain pass. But with just a few modifications, the Kims’ plight could easily have been the Glicksteins’.

[This secton incorporates text originally written in May 2004 for a similar topic on my high school alumni mailing list.]

I think I understand the need of some to make those pompous pronouncements. I know what drives the desire to blame the victim.

Several years ago I got involved in flying. A big part of what a pilot does when not flying is to talk about flying. And read and write about flying. Specifically, there are a few flying magazines that many pilots read. You’ve seen them on the newsstands: “Flying,” “Plane and Pilot,” “AOPA Pilot,” “Private Pilot,” etc.

These magazines are highly formulaic and the writing is uniformly awful. Every month it’s the same test drive of a cool new plane, the same product reviews, the same reports of what our pilot buddies in Congress are doing for us, and the same fights between local airports and the noise-averse communities surrounding them. There’s no doubt in my mind that every pilot skims right over all that junk to head straight for the monthly column about some horrible aviation mishap (columns with names like “Never Again” and “I Learned About Flying From That” and “Aftermath”).

It’s a truism that there’s a little nugget of fear somewhere deep inside every pilot. The accident statistics are very favorable, but of course it’s the grisly stories that stand out in one’s mind. So pilots morbidly devour every accident story, mainly looking for reassurance that they’re immune to whatever mistake that poor bastard made. Didn’t get an updated weather briefing before takeoff? Idiot. Didn’t do his weight-and-balance calculations? Moron. Didn’t budget enough fuel for getting to his alternate landing site? Allowed an impatient controller to bully him into a bad decision? Didn’t heed the rough sound coming from the engine? I’d never do that.

I feel sorry for the victims I read about in those stories, but I freely admit to playing that blame-the-victim game as I read. Usually the mistakes are simple and understandable. Sometimes I can’t find any difference between that poor bastard and the cautious way that I fly, other than dumb luck, and that’s pretty unsettling. But sometimes the lapses in judgment are so egregious that it turns any sympathy I may have felt into impatience, even anger, especially when there are innocent victims involved.

Maybe this is something like how the Monday-morning wilderness quarterbacks are reacting to the Kims’ story. To me, the Kims’ mistakes fall into the simple-and-understandable category. (All too understandable.) For others maybe they are egregious. Seems harsh to me, but at least I can understand it as a difference of degree rather than a difference of kind.

In recent years, when contemplating my own mortality, I’ve found that it’s not me I worry about (as it was when I was younger), it’s the people I’d leave behind. This was true even before I became a parent but is a hundred times truer now. As long as I don’t die stupidly, it’ll be without any serious regrets. (Well, I would like to know how the Harry Potter series turns out.) But I have a strong stereotype in my mind about what losing a father at a young age can do to a couple of boys like Jonah and Archer. In that stereotype they become sullen, mad at the world, unambitious, even self-destructive. This more than anything else is why I hope not to die. There’s an alternate stereotype, where the survivors pull together to endure the crisis and emerge more tightly knit for their loss. This more than anything else is what I hope for the Kims.

Random security thought

As I was reading a passage earlier from “The System of the World” (volume 3 of Neal Stephenson’s amazing Baroque Cycle) about 18th-century Londoners taking precautions against highwaymen, a thought struck me: when my credit cards expire, I dutifully cut them up and discard them. Why not instead use them to populate a decoy wallet? That way if I’m ever mugged, I just hand over the decoy wallet containing a few expired credit cards, a few bucks, and maybe a phony driver’s license with a false address.

Eh, I’m not really paranoid enough to put this together (not to mention carry two wallets all the time), but if you are and want to use my idea, more power to you.

(Even better: learn magic.)

East is east and west is west

…and when it comes to varieties of Entenmann’s cakes, never the twain shall meet.

When I lived in New York (now more than half a lifetime ago, egad), my two favorite varieties were “Thick Fudge Golden Cake” and “Filled Chocolate Chip Crumb Cake.” But when I went to Pittsburgh for college, those cakes could not be found anywhere; nor (as I later discovered) are they available in California. This despite the fact that many other Entenmann’s varieties are available nationwide.

When I lived in New York (now more than half a lifetime ago, egad), my two favorite varieties were “Thick Fudge Golden Cake” and “Filled Chocolate Chip Crumb Cake.” But when I went to Pittsburgh for college, those cakes could not be found anywhere; nor (as I later discovered) are they available in California. This despite the fact that many other Entenmann’s varieties are available nationwide.

As if I have nothing better to do with my time, recently I decided to investigate. The Entenmann’s website sent me to the Entenmann’s distributor for the California region, an outfit called Bimbo’s Bakeries USA in Fort Worth, Texas. (That’s the second thing I’ve run across called Bimbo’s having nothing to do with actual bimbos, which is two more than I would have expected to find if you’d asked me.) I sent a polite and eloquent letter inquiring about the unavailability of these varieties in regions other than New York.

As if I have nothing better to do with my time, recently I decided to investigate. The Entenmann’s website sent me to the Entenmann’s distributor for the California region, an outfit called Bimbo’s Bakeries USA in Fort Worth, Texas. (That’s the second thing I’ve run across called Bimbo’s having nothing to do with actual bimbos, which is two more than I would have expected to find if you’d asked me.) I sent a polite and eloquent letter inquiring about the unavailability of these varieties in regions other than New York.

Superpest

Sometimes, achieving a satisfactory outcome required persistence. My mom had it in abundance, as dozens of public-relations officers learned over the years to their occasional dismay. One of her favorite tricks, when on the phone with some peon who was trying to stonewall her or brush her off, was to say dismissively, “You obviously don’t have the authority. Let me talk to your supervisor.” The peon caved in to my mom’s demands nine times out of ten, just to prove her wrong.

In such ways did my mom eventually adopt the moniker “Superpest.”

When I was growing up, my mom was the undisputed champion of writing letters to companies, both to complain and to praise. In those good-old-days of corporate public relations, she almost never failed to receive both a polite, personalized reply and a handful of discount coupons for the company’s products, if not outright free samples. And very often, if the letter was a complaint, the company fixed the problem, e.g. by sending a refund.

These are no longer those good old days. The reply from Bimbo’s stated: “Those varieties are not available in your market.” Yeah, I know, that was kind of the point.

I was planning to look into the matter further, but (a) I do have better things to do with my time, and (b) Amazon.com started selling Entenmann’s products from Gristede’s in New York! So now I can get my old favorites again. Which isn’t necessarily a good thing.

Now if only I can find good Italian ices…

Alone again, finally

Last night was the iPost Christmas party at the four-star Hotel Monaco in San Francisco. Our friend Laura brought her niece Amelia to our place for a sleepover with Jonah and Archer. (She’s right between them in age. We joke that Jonah and Archer will fight over her when it’s time to choose a date for the prom.) This freed up me and Andrea to go to the party (in formal dress!), drink more than usual, hang out with folks until all hours, then retire to our room upstairs (on iPost’s dime) and spend the night completely alone. For the first time in over four and a half years!

Naturally we worried about how the kids would handle their first night with neither parent. We needn’t have — they both did great.

We knew it would be wonderful to spend a completely grown-up night, but it exceeded even our high expectations — as did Laura and her magic touch. (It’s Laura we adore-a. It’s Laura the world needs more o’.) And you can do a lot worse than spend an elegant evening being treated like royalty in the gorgeous Hotel Monaco (another eye-popping Kimpton hotel — we’ve stayed at their Argonaut and their Triton too and have loved them all).

Now the question is: Is this the shape of things to come? Or will last night have to tide us over for a few more years?

Words to live by

When my dad was in his forties he loved a book by Jules Feiffer called Tantrum, about a middle-aged man named Leo having a mid-life crisis. His life has too much responsibility and too little fun and he throws a tantrum, willing himself back to age two! He spends most of the rest of the book looking for someone willing to pamper and baby him.

A new edition of that book was among the gifts from my dad when I turned forty myself recently. It’s witty and well-observed, if a bit depressing. You don’t have to be having a mid-life crisis to appreciate it.

A new edition of that book was among the gifts from my dad when I turned forty myself recently. It’s witty and well-observed, if a bit depressing. You don’t have to be having a mid-life crisis to appreciate it.

In one scene, two-year-old Leo encounters an authentic two-year-old at an airport. Having by this point in the story suffered several rejections — everyone’s got their own problems (which is more or less the whole point of the book) — Leo bitterly tells the other boy, “If I knew at your age what I’ve learned with grief since… don’t thank me, just listen,” and then offers this advice:

- Get the grades, but don’t trust what they teach you.

- Don’t tell them what you’re thinking; they’ll use it against you.

- Never be rational if you want to have your way.

- Ignore logic; it’ll cripple your spirit.

- Look out for abandonment by your loved ones.

- Don’t be horny after marriage.

Then, as the other boy walks away to board a flight with his family,

- Don’t mature! Mature people do the shit work!

The nature of reality, part 2: Dimensions

In part 1 of this occasional series (well, it’s a series now), I wrote:

It’s as if I decided to write an elaborate computer program to simulate a universe, complete with its own laws of nature and its own intelligent life. In time those beings might figure out all the rules of their universe, but what chance would they ever have of guessing what I’m like, or the nature of the computing hardware in which they are abstractions? The copper and silicon and tiny electrical charges of which they’re really composed would appear nowhere at all inside the simulation. The rules by which their universe operates would bear no resemblance to the rules of the programming language in which I expressed them.

Nevertheless, physicists (human ones) are making attempts at guessing at the nature of the computing hardware in which our reality is an abstraction (if we can agree to think about it that way for now). One of the more well-known guesses is a very complicated idea called string theory. Famously it declares that our universe is not merely three-dimensional, it’s actually ten-dimensional. The hell?

To understand what ten-dimensional space can possibly mean, and how it jibes with the universe-is-just-a-computer-program metaphor, let’s first make sure we understand three-dimensional space.

What does it mean to say that space is three-dimensional? Put simply, it means that three numbers are necessary to identify your location — for example, latitude, longitude, and altitude. Two numbers won’t do it.

It also means that three numbers are sufficient to identify your location (if you choose the right three). You don’t need more. You could tell someone, “I’m at the corner of 34th Street and 5th Avenue on the 57th floor where the ZIP code is 10118 and there are 28 days left before my next birthday,” but some of those numbers will be redundant and/or irrelevant for locating purposes.

Finally, the three numbers that are necessary and sufficient for locating you are also independent of each other. You can change your latitude without changing your altitude. You can change your longitude without changing your latitude. You can change your altitude without changing your latitude or your longitude. (For that you probably need a helicopter. Or to be plummeting out of the sky.) Of course you can also change the numbers together in any combination — e.g., changing both your latitude and longitude at the same time by going northwest instead of due north or due west. You can, but the point is that you don’t have to.

Back to ten-dimensional space. If our space is really ten-dimensional, like string theorists say it is, wouldn’t that mean that three numbers don’t suffice to describe our position? Well, yes, it would; we’d need ten numbers. But this contradicts our everyday experience, which tells us that three numbers really do suffice.

String theorists counter this by saying that seven of the ten dimensions are really really small. The hell? Small dimensions? Isn’t a dimension the same as a direction? (E.g., north/south; east/west; up/down.) How can a direction be small?

To understand what a small dimension is, let’s switch to computer programming for a moment. A big part of programming is modeling objects, which means representing something in terms of numbers and other kinds of digital data. Suppose, for instance, that I’m writing a weather-predicting program and that among the things I need to model is a cloud. What are the essential properties of a cloud that my program would have to model?

- Its height above the ground;

- Its latitude and longitude;

- Its volume (how big it is);

- Its moisture content (thin and wispy, or dense and puffy?);

- Its temperature;

- Its electrical charge (for predicting lightning);

- Size change: currently growing, shrinking, or stable.

(Disclaimer: I’m no meteorologist, I don’t really know how you’d model a cloud in software, but this looks good for our purposes.)

A cloud’s latitude and longitude can vary enormously — the cloud can be situated over any point on earth! But its height above the ground can range only from 0 to a few miles. And its “size change” property can contain only one of three values. If you think of each of these properties as a dimension, then it’s easy to see how latitude and longitude are “big” dimensions, height is smaller, and “size change” is really tiny.

What? You can’t think of those properties as dimensions? Why not? Each one is arguably necessary for describing the cloud; collectively they are sufficient for describing the cloud (let’s assume); and each property is independent of the others, able to vary on its own. As we agreed earlier, those are the requirements for calling something a dimension. So by that definition, this cloud is eight-dimensional.

Even so, if you omitted the smaller dimensions — the ones that can’t vary much, such as “size change” and “temperature,” say — you’d still know a lot about the cloud. You’d have a six-dimensional approximation to what’s really an eight-dimensional object. Most of what you usually need to know about a cloud can be discerned from that approximation — where the cloud is, roughly what it looks like, and so on. There are some things that would be harder to predict about it, such as whether it will rain on you and whether flying through it will cause ice to form on your wings. A fuller description of the cloud would make those things clearer. But you can still do a lot with just six of those eight dimensions.

That’s my analogy to ten-dimensional space, where seven of the dimensions are really small. The three big dimensions are enough to describe everything in our ordinary experience, but there are details of reality that only become clear when you add in the others. (That’s assuming that space is ten-dimensional — string theory is just an unproven hypothesis, after all, and other competing theories have other things to say about the number of dimensions we inhabit.)

If string theory’s right, and if our universe really is running as a simulation inside some sort of computer — two enormous “ifs” — then the cosmic computer programmer who invented our universe found it necessary to use ten numbers to model the position of each fundamental particle. That ten-dimensional machinery gives rise to what we perceive as three-dimensional reality. That’s not such a strange thought, after all. Haven’t you ever used three-dimensional machinery to create a two-dimensional reality?

One red cent

I started this blog in July, and in hopes of defraying expenses I added Google Adsense ads to it not long after. (You have to view individual blog posts to see the ads, e.g. by following this link; they aren’t visible on the front page.)

I don’t have the most widely read blog, but I do OK. I get several pageviews a day, amounting to thousands of pageviews since this blog has been up and running. Guess how much AdSense revenue I’ve earned in all this time? (Hint: see the title of this post.)