If

the opposite of love is not hate but indifference, then I guess I’m not really

“over” Star Wars, because I just can’t contain my frustration at how awful

The Empire Strikes Back is.

(Yes, I am again going to tell you why you shouldn’t like a movie as much as you do.)

I watched Empire again for the first time in in a decade with my kids last week. Since they discovered Star Wars a couple of years ago, I have kept the lid on the existence of the sequels and the prequels, hoping to keep their experience of the Star Wars universe “pure” for as long as I could. Star Wars is perfect in its way; all of the other films merely detract from it.

Besides, if I had to wait years between installments, it won’t kill my kids to.

Keeping the other films secret did not prevent Jonah from learning in the schoolyard that Darth Vader is Luke’s father, among other things. I finally let the cat out of the bag (about the existence of episodes V and VI — I am not yet ready to let episodes I through III destroy my sons’ souls) when Andrea bought tickets for me and Jonah to go see the One Man Star Wars show later this month. To enjoy it, Jonah will need to know the entire original trilogy.

The secret of Star Wars’ success

In its 1977 review of Star Wars, Time magazine wrote:

Star Wars will find itself competing with several other major movies for the attention of audiences this summer, almost all of them with much bigger budgets. […]

Despite the talent and the money arrayed against it, Star Wars has one clear advantage: it is simple, elemental, and therefore unique. It has a happy ending, a rarity these days.

“A rarity these days”? In appreciating the impact of Star Wars, it is necessary not only to imagine what the state of the art in special effects was in 1977. (Check out Logan’s Run next chance you get. It won the Oscar for special effects shortly before Star Wars came out. That was the painfully cheesy state of the art.) It is also essential to remember that the ’70’s before Star Wars was a bleak time for movies a time for bleak movies. With the old studio system almost fully dismantled, a new generation of auteurs making important or disturbing or very personal films, and a new generation of stars more comfortable playing antiheroes rather than heroes, the movies were generally not a place you went for an uplifting good time. But boy did audiences need escapism — Vietnam, Watergate, the energy crisis, and a recession were all current or recent memories. This is the cultural niche that Star Wars explosively filled. How many dozens of “simple, elemental” fantasy films have followed? Star Wars was the first. Can you imagine a moviegoing world where no such thing had existed for a generation? Can you now imagine how the arrival of such a film, at such a time, would thoroughly dominate the popular imagination for years to come?

The Time article quotes George Lucas as saying,

It’s the flotsam and jetsam from the period when I was twelve years old […] The plot is simple — good against evil — and the film is designed to be all the fun things and fantasy things I remember. The word for this movie is fun.

Later, George Lucas would come to believe, and repeat ad nauseam, his own press about the mythic archetypes and timeless themes in his space saga. It’s all a lot of hooey. Star Wars succeeded because it was kid stuff in a world grown too adult.

I can’t fathom those who claim Empire is the best of the series. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that Star Wars was light entertainment — indeed, that was the key to its success — whereas Empire strove to be something else — something deeper, more adult. For reasons I’ll go into below, it did not succeed. It was a mistake even to try. But the fact that it did try may render Empire more worthy, in the minds of some, for serious consideration.

In 1980, I was the biggest Star Wars fan that my friends and family knew. My friend Sarah and I played hooky from school on May 21st to wait hours in line for the first show of Empire at the Loews Orpheum on 86th Street in Manhattan. Afterward, everyone wanted to know what I thought.

I couldn’t admit the truth to them: that I didn’t like it. I couldn’t even admit it to myself. To do so would be to renounce my identity as a Star Wars fan — at that young age, the only identity of any kind I had yet managed to acquire beyond standard-issue “bright young man.” Besides, there were just enough thrills in the movie to confound my true feelings. I quickly zeroed in on an official line, which I repeated whenever anyone asked me how I liked Empire — since Episode V ended on a cliffhanger, I was reserving judgment until Episode VI.

The problems with Empire begin in the very first line of dialogue. Luke Skywalker tops a snowy rise on his tauntaun, unmasks himself in a closeup, pauses for applause, and speaks into his radio: “Echo Three to Echo Seven. Han, old buddy, you read me?”

Now, the story is that the rebellion has just moved its base to this new planet and is busy setting up shop and scouting out the area. Luke and Han are two of the leaders of this effort. Presumably they see each other multiple times every day, coordinating the hundreds of details involved. If you were Luke, would you address Han as “Han, old buddy” if you’d seen him just a few hours before? No, it would be, “Hey, you there?” “Old buddy” is how you’d address him if you hadn’t seen or spoken to him in a few years — just as the original audiences in 1980 hadn’t. Luke isn’t hailing his coworker, he’s reintroducing him to the audience. The fourth wall is broken.

A few moments later, Han himself rides into the new rebel base. Dismounting his tauntaun, he too unmasks himself and gazes past the camera for a moment while the applause subsides. He next strides pointlessly over to his ship to say something meaningless to Chewbacca and then walk away, all so Chewie can have his own applause moment. And an instant later it’s Leia’s turn to pose silently for the camera for a moment.

What is this, a movie or a fan convention?

Now the wampa subplot gets underway. Here it is in a nutshell: Luke is abducted by an ice monster, escapes, and is rescued.

The dramatization of this subplot is almost as uninteresting as that synopsis. (Han Solo appropriating Luke’s lightsaber to slice open the dead tauntaun and stuff Luke inside is what earns the “almost.”) It has no bearing at all on anything else that happens in the film, or the trilogy for that matter. Why is it even included? The answer has long been known to Star Wars fans even as George “the filmmaking technology of the 1970’s prevented me from showing Greedo shooting first” Lucas has denied it: Mark Hamill’s face was disfigured in a car crash after Star Wars, so they needed a way to explain his changed appearance in the new film. Their answer: a wampa paw in the kisser, story cohesion be damned.

A rebel officer cautions Han Solo against venturing out into the inhospitable Hoth night to look for Luke. “Your tauntaun will freeze before you reach the first marker!” Han Solo’s response is both inappropriate and out of character:

“Then I’ll see you in hell!”

This is something you’d say to your enemy, not to someone giving you sensible advice! It’s also the only intrusion into the series of earthly religious ideas, and weirdly out of place for that reason.

Next up in this target-rich environment: the aftermath of Luke’s ordeal. As he recuperates in the infirmary, it’s time for a little levity. Empire delivers it in the form of sophomoric name-calling.

Leia: I don’t know where you get your delusions, laser-brain.

Chewbacca: [laughs]

Solo: Laugh it up, fuzzball.

All of which culminates in this outburst from Princess Leia:

Why you stuck-up, half-witted, scruffy-looking nerf-herder!

Guffaw.

Now, I can appreciate the value of a good name-calling insult, thou unmuzzled ill-breeding lewdster. But come on. “Laser-brain”?

I’ll give George Lucas a pass on the icky climax of the infirmary scene, where Leia smooches her twin brother just to get a rise out of Han Solo, because Lucas (by his own admission in a 1983 interview) didn’t know he would end up making Luke and Leia siblings until halfway through writing Episode VI. On the other hand, maybe he doesn’t get a pass. Shouldn’t he have had a central plot element like that planned out in advance? And what does it say about Leia’s maturity that she’d toy with Luke in this adolescent way?

Well, let’s move on. Soon Luke is all better, and just in time to face an Imperial invasion. On the way to his snowspeeder he bids Han Solo farewell. As Luke walks away, the camera lingers on (what can only be described as) Han’s strangely loving gaze. We knew he had a soft spot in his outlaw’s heart, but when did he turn into a sentimental sap?

Later, after a thrilling land battle in which Luke crashes his snowspeeder but buys time for many rebels to escape, Han Solo is making his own escape, but… the Millennium Falcon‘s hyperdrive won’t work! On the one hand, that’s good, ’cause it means it’s time for a thrilling chase through a nearby asteroid field. On the other hand, what do you mean the hyperdrive won’t work? Did an angry wampa tear it apart looking for Luke (which would at least have tied the pointless wampa story into the rest of the plot)? No, it just plain broke.

We’re supposed to believe that the Falcon is the hottest smuggling hot-rod in the galaxy, and Han Solo is a wizard at wringing every drop of performance out of her. Yet somehow the hyperdrive was broken for no reason — and Han Solo had no idea? Oh well, it happens to the best of us, I guess, and the asteroid field scene is cool, no doubt about that.

But what’s the very next thing that happens? Luke crashes his X-Wing on Dagobah — also for no reason! Hotshot pilot my ass. For those keeping score, that’s two Luke crashes within about ten minutes of screen time. Not only are our heroes suffering a collective and inexplicable loss of mojo, but considering Mark Hamill’s real-life ordeal it’s in pretty poor taste for the screenwriters to keep pressing the “Luke crashes” button.

Fortunately for Luke, the one person on all of planet Dagobah he has come to see is within a soundstage of the crash site. Whew!

When Yoda reveals his identity to Luke, he chides his motives. “Adventure. Excitement. A Jedi craves not these things!” This is where Luke should have said, “OK, seeya, thanks for the soup.” In the movie-and-a-half leading up to this scene there is not one thing we know about Luke beyond his desire for adventure and excitement. Well, maybe his desire to know more about his father, but that in itself wouldn’t make him yearn to be a Jedi any more than I yearn to be a bookbinding salesman.

And by the way, what’s wrong with craving adventure and excitement? Yoda never says. He does say that Luke is filled with much anger. Really? Luke? Luke Skywalker? When Luke tells Yoda he’s not afraid, Yoda promises him mysteriously, “You will be. You will be.” Huh? Is Yoda in the same movie as everyone else?

I’d like to turn our attention away from Dagobah for just long enough to make this observation: with hundreds of ships and thousands of fleet personnel at his disposal, why, exactly, does Darth Vader think he’ll have better luck capturing the Millennium Falcon by putting a tiny handful of bounty hunters on the job? Fortunately for the bounty hunters, when the Imperial fleet finally flushes the Falcon out of the asteroid field, her hyperdrive is still busted. Han Solo’s repairs aren’t worth spit (and baling wire). Groan.

Back to Yoda, who implores Luke to stay on Dagobah until his training is complete. “Only a fully trained Jedi knight, with the Force as his ally, will conquer Vader and his emperor.” Ben opines that Luke is their “last hope.” Two things about this: first, what do Ben and Yoda think a greenhorn like Luke can do alone against the Empire that they themselves could not have done better together years earlier, before the Empire amassed its present might? And second, if everything depends on Luke, why in the world did Ben wait so long to begin Luke’s Jedi training?

Ben makes a last plea to Luke: “If you choose to face Vader, you will do it alone. I cannot interfere.” But… but… you already have interfered! You got Luke to go to Dagobah! You persuaded Yoda to train him! So obviously you can interfere, you just choose not to. But if Luke is your last hope, you damn well better interfere! What, is Ben making an empty threat? Is he throwing a tantrum? None of this makes very much sense. And what about Yoda? Can’t he lend a hand? He’s a freakin’ Jedi Master, for crying out loud.

No, for some reason, Luke is all on his own. He leaves Dagobah and heads to Cloud City, where our other heroes are prisoners. Darth Vader is using Luke’s friends as bait to trap Luke, which is well and good, but then he plans to… freeze him for his journey to the Emperor? Why does he feel the need to do something bizarre like that? We never find out. Can’t a dark lord of the Sith and a jillion stormtroopers safely imprison an incompletely trained Jedi for the duration of a single interplanetary trip?

Whatever. This gives us the chance to see Luke trying to hold his own against Vader in a series of pretty cool duel scenes. Vader’s psychological assault on Luke and the decision Luke faces are the only parts of “deeper, more adult” in the film that do work.

Enough bashing of individual moments in the film. Let’s look at some of the bigger problems.

The first is a personal complaint concerning the differences in the Force between the first film and the second. In Star Wars, the Force can be seen as an allegory for self-confidence, an idea that has held great appeal for me my whole life. Anyone can become proficient with “the Force” just by honing and believing in their own abilities. In Empire (and the rest of the series) that idea is out the window. The Force is something that runs in families — if you ain’t got it, that’s too damn bad — and you can do magic with it, and Forcey good guys can come back as ghosts to keep their old Forcey friends company. (Yes, in Star Wars, Luke hears Ben’s voice after Ben dies. But like the “ghosts” in Six Feet Under, Ben’s voice gives Luke no new information, so is it really Ben’s ghost saying encouraging things to Luke or is it just Luke’s memory of Ben’s training? That ambiguity plays better, for me, than Ben’s floating, spectral form [complete with the cloak that was left behind when he died] having conversations with people.)

My next big complaint is that the story is too small. It’s all about Darth Vader being obsessed with Luke. The Empire hardly does any striking back! The first movie was about a galaxy in turmoil; this one’s about a small group of people.

What if the Empire really did strike back in this film? Luke, on a cocky high after lucking into a major rebel victory, would be horrified to witness the awesome power of the Empire as it brings all its resources to bear and eradicates nearly every vestige of the rebellion. Somehow managing to survive the galactic holocaust, Luke retreats into obscurity — echoes of Ben Kenobi! — utterly demoralized and haunted by what he’s seen and (indirectly) caused. Eventually he befriends a local starry-eyed farmboy with dreams of adventure, and at first tries to knock the wanderlust out of him. But in the end it is his own sense of duty and derring-do that is reawakened. (Episode VI could then have been about the two of them building a newer, stronger rebel alliance that finally does topple the Empire. Oh well. This is not the first time — or the second — that I’ve thought I could do the story of Star Wars better myself.)

Say what you will about Return of the Jedi — the irksome Ewoks, the perfunctory return visit to Dagobah (and its oversized helping of exposition), the broken-record reuse of the Death Star as the military objective, and the way the rebellion seems to hand out generalships like candy — it was fun to see Luke kick ass, to see Threepio revered, to see the Emperor dominate Vader, to see Leia in a bikini. Fun is what Star Wars was supposed to be about. Maybe George Lucas, the famous film rebel, was rebelling against the success of his own creation, but for whatever reason, The Empire Strikes Back was no fun at all.

A little later, while we were watching another episode, Andrea came home. I asked her, “Can you guess whose voice that is doing the narration?”

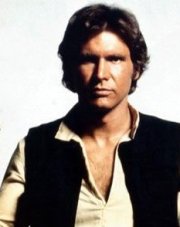

A little later, while we were watching another episode, Andrea came home. I asked her, “Can you guess whose voice that is doing the narration?” Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen.

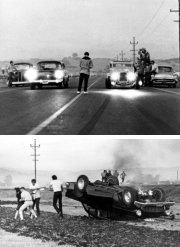

Jones tries to convince Falfa to accompany him on a highly unique project. Mysteriously, Jones tells Falfa that he can divulge no details (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you”) but, knowing Falfa’s love of fast cars, promises him the chance to drive something faster than anyone’s ever seen. This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process.

This was the wrong thing to say. Bob Falfa’s pride is hurt; his own car, he asserts, is the fastest thing on wheels. “And I’ll prove it to you!” Falfa storms off before Jones can get another word in and, almost at once, he goads a local hood, John Milner, into a drag race — which Falfa loses, spectacularly, trashing his car in the process. Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away.

Late one night Stett finds himself in a high-stakes poker game with some hardcore gamblers, including one charming out-of-towner (“I’m just passing through”) who’s losing badly. Out of funds on a big hand, the stranger puts his pink slip in the pot, assuring everyone that it’s for “the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy.” Stett wins the hand — and learns to his astonishment that he’s the new owner of a spaceship called the Millennium Falcon. The stranger, Lando Calrissian, is devastated but gracious in defeat. He offers to give piloting lessons to Stett in return for a lift back to his home galaxy far, far away. Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction.

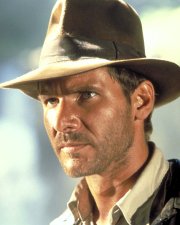

Feeling nostalgic one day, Solo takes a long flight back to Earth and is a little puzzled to discover that, due to the time-distorting effects of faster-than-light travel, he has arrived years before he left. Thus unable to visit his old stomping grounds — they don’t exist yet! — he makes to leave immediately but the Falcon’s hyperdrive, which has always been finicky, gives out altogether. Solo is stranded on a planet where there are no spare hyperdrive parts for thousands of light years in every direction. Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947.

Solo begins hunting for Etruscan artifacts all over the world and is soon drawn into the world of archaeology, for which he has adopted yet another new alias — Indiana Jones — and reindulged his old love of broad-brimmed headwear. Along the way he has numerous new adventures and his repair of the still-concealed Millennium Falcon is sidetracked into an on-again, off-again project whose highlight is a dramatic near-crash during a test flight in 1947. In

In  All of which was interesting enough to think about that it prompted me to begin writing this blog post, which in turn prompted me to look up

All of which was interesting enough to think about that it prompted me to begin writing this blog post, which in turn prompted me to look up  To my surprise, nearly all of the cast had zero, one, or two additional film credits after Bugsy Malone, and that’s all. Scott Baio played the title role, and he of course enjoyed

To my surprise, nearly all of the cast had zero, one, or two additional film credits after Bugsy Malone, and that’s all. Scott Baio played the title role, and he of course enjoyed